About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

To the enthusiast of classic lightweight and vintage bicycles, few component makers evoke as much prestige and technological reverence as Mavic. Familiarity, too. Established in Lyon, France, in 1889, the company’s history is inextricably linked to the evolution of road cycling itself, predating even the Tour de France by over a decade. As we look back at the company’s first century—from its humble origins to the high-tech aero revolutions of the 1980s—we find a history defined by a relentless pursuit of speed, reliability and an unyielding willingness to stand by everyday cyclists everywhere, even if by trickle-down innovation that originates in the professional peloton.

The Mavic story began when Charles Idoux and Lucien Chanel entered the spare parts business for the new but burgeoning bicycle market, creating Manufacture d’Articles Vélocipédiques Idoux et Chanel (MAVIC) in 1889. Simultaneously, brothers Léon and Laurent Vielle established a metal plating business, Établissements Métallurgiques du Rhône (EMR), which operated the AVA brand that would come to be known for its mid-20th century handlebars and stems. Both companies shared a common CEO named Henry Gormand, who purchased Mavic in 1920 and would combine the two company’s resources to develop the aluminum bicycle rim in 1926.

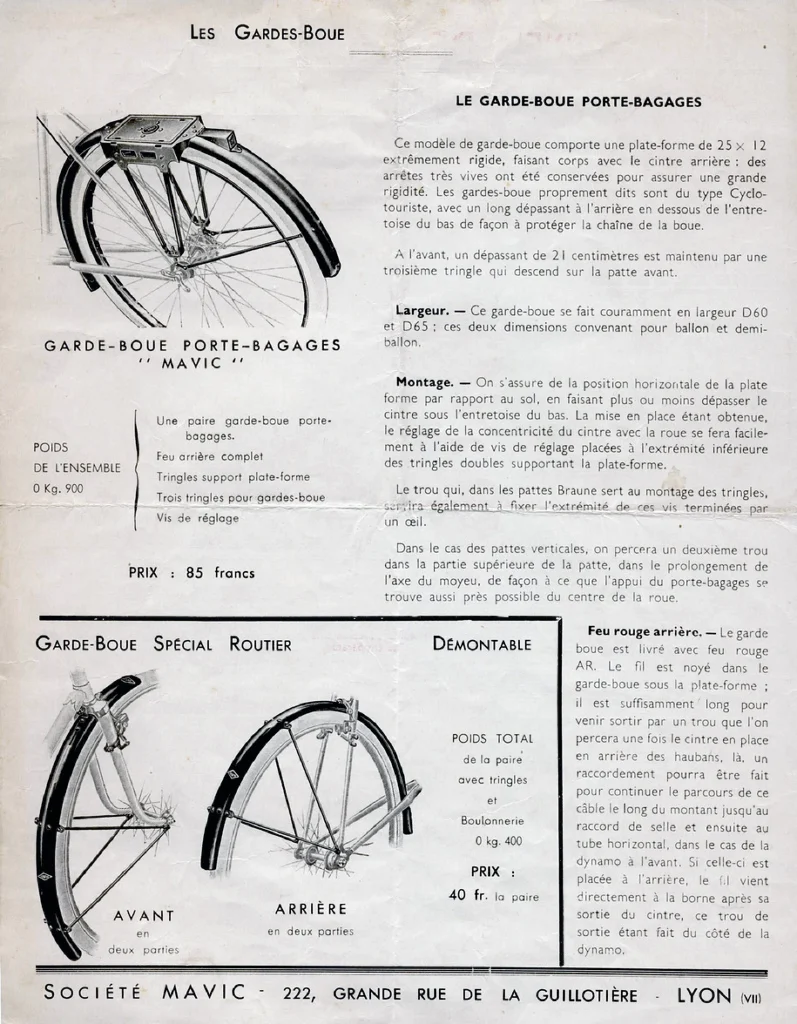

In these early decades, Mavic was primarily known for accessory products. Their flagship was the “Bavolet” apron mudguard, introduced in 1934. This design took the standard mudguard and added a flexible rubber apron to the trailing edge to deflect water and mud away from a rider’s shoes – an innovation that remains a staple today for commuters in inclement weather. (Between the Bavolet and galoshes, one’s feet are virtually guaranteed to remain dry on your rainy ride to work or school.)

Mavic also displayed an early flair for “rollables” by manufacturing exquisite children’s pedal cars in the 1930s. Models such as the “Championnat” and “Tout Temps” were exceptional for their time, featuring spoked wheels with decorative hubcaps, chain drives to the rear axle, soft tops and rear trunks. While these endeavors were brief, they demonstrated the company’s interest in all things pedal-worthy, seeking product-market fit in whatever direction their materials, tools and inspirations could take them.

The company’s most significant leap forward in rim design occurred in 1934 with the introduction of the Dura model. At a time when wooden rims weighing 1.2kg were the standard in the professional peloton, Mavic developed a hollow rim made of lightweight Duralumin—an alloy of copper and aluminum—that weighed a mere 750g. This rim pioneered the use of double eyelets, which acted like small tubes to support and distribute spoke tension across both the lower and upper walls of the rim.

Given this is the unpredictable bicycle market we are talking about here, regular readers of Ebykr will remember all too well that nothing comes easy in bikeland. True to form, a strange fluke at the patent office brought about by a shared vision for rim design held by two strangers separated by hundreds of kilometers jeopardized the successful launch of this breakthrough product. An Italian designer named Mario Longhi registered an identical “double eyelet” patent just two hours before Mavic on January 5, 1934. Fortunately for all involved it would seem, Longhi allowed the larger and more capable French company (and another Italian company named Fiamme) to exploit the technology under license until 1947.

Because metal rims were banned by the Tour de France in favor of wooden rims at the time, the event’s 1931 winner Antonin Magne trialed them in secret during the 1934 edition of the race. His trick? The trial rims were painted to look like wood to avoid detection by race marshals. Magne’s subsequent 27 minute margin of victory signaled the end of wood’s dominance as a bicycle rim building material. By 1935, every rider in the Tour was using Dura rims.

Early use of Dura rims was not without its controversy. A Spanish racing cyclist named Francisco Cepeda died during a descent of the Galibier in the 1935 edition of the Tour de France while riding on Mavic Dura rims. Mavic was initially accused of equipment failure, though they were cleared by authorities when the blame shifted to the gluing of the tubulars. The incident forced the company to launch a major press campaign to restore its reputation after its breakthrough aluminum rim innovation was accused of being a “deception” and prone to failure.

Around this time, Mavic and AVA (which primarily manufactured aluminum handlebars then) started conducting combined advertising campaigns. These efforts reflected a unique corporate synergy between the companies under Henry Gormand’s unified leadership. This joint advertising partnership lasted for three full decades, from 1934 to 1964. The middle of this era also saw the first Mavic logo change, as the original 1923 circular logo was replaced by the famous diamond shape in 1945, which then endured until 1988 when it was replaced by a logo featuring slanted black “MAVIC” text centered in a simple yellow parallelogram. You know the one, which is probably seared in there by now.

In 1964, CEO Henry Gormand’s son, Bruno Gormand, took over the leadership at the company, ushering in a new era of passion for performance. The most visible manifestation of this was the birth of the “Yellow Fleet” of neutral assistance vehicles. The concept was born in 1972 when Gormand lent his own car to a team director whose vehicle had broken down during the Critérium du Dauphiné.

By 1973, Mavic officially launched its “neutral and free” assistance service at Paris-Nice. This revolutionized racing – where a mechanical failure once meant the end of a rider’s race, Mavic now provided spare bikes, wheels and even a radio link service for organizers and doctors. The mechanics took this “Service Courses” role very seriously, training in the factory yard to bring rear-wheel change times down from 30 seconds to just 15 seconds and front wheel changes to a blistering 10 seconds. For riders like Laurent Jalabert, the yellow car also served as a tactical marker. If the car was allowed into the gap behind a breakaway, the riders knew they had established a significant lead, just as it remains today. In characteristic Mavic fashion, the company followed up with the first neutral assistance motorcycle—a yellow Honda XL 600—at Paris-Nice in 1984, some 11 years after the first car was launched at the same race.

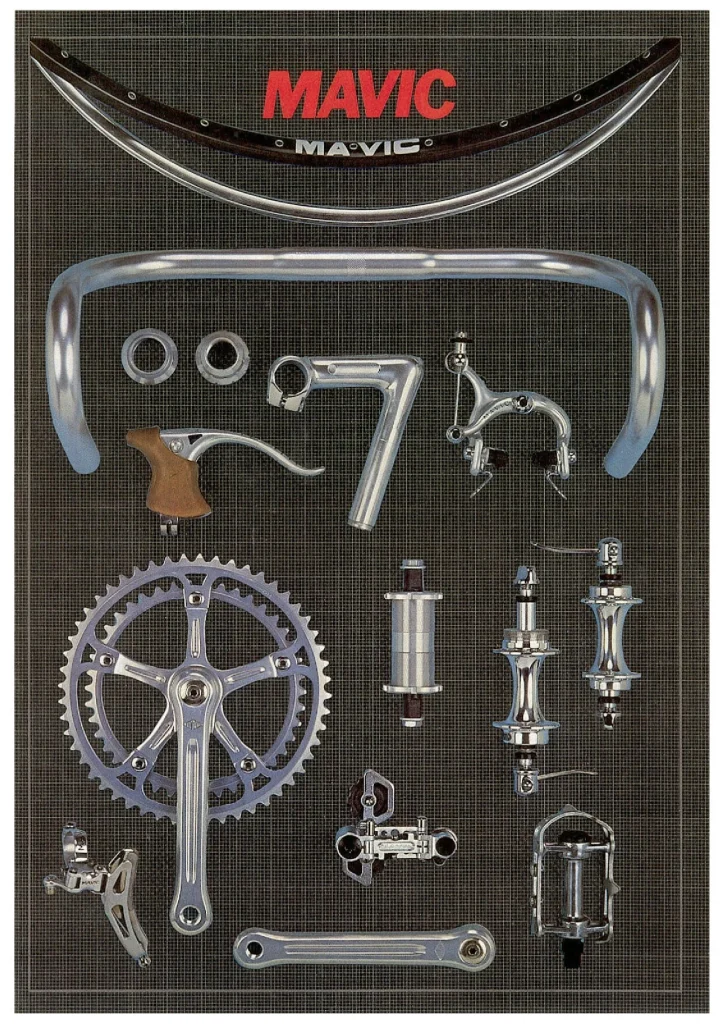

The mid-1970s cemented Mavic’s reputation for innovation in materials and componentry:

Mavic’s engineers were early pioneers of wheel aerodynamics, drawing inspiration from cycling studies at the French Study Bureau as early as 1973. This research produced the first fiberglass lenticular (biconvex) wheel, the first-ever to bear the Mavic signature, though race regulations initially prohibited its use. The company saw its peak market dominance in 1978, when it produced 4,000 rims per day, held a staggering 65% of the world market share and equipped 25 professional racing teams. By 1979, Mavic partnered with Gitane-Renault to produce the Profil bike, an aero road machine featuring modified tube shapes and deep-section Mavic CXP25 alloy rims. Bernard Hinault rode this bike to win four individual time trials and the final yellow jersey in the 1979 Tour de France. The aero wheel race was officially on!

The 1980s saw the commercialization of these studies with the 1985 launch of the Comète carbon fiber disc wheel. Utilizing a lenticular shape to slice through the air more efficiently than flat designs, it became an immediate necessity for time trial specialists. The subsequent “Comète + and -” version even featured 12 cells around its periphery where riders could add steel ballast (130g to 780g) to suit the demands of specific events. Perhaps its most famous application was in 1989, when Greg LeMond utilized the Comète and Tout Mavic system to secure his legendary eight-second victory in that year’s Tour de France.

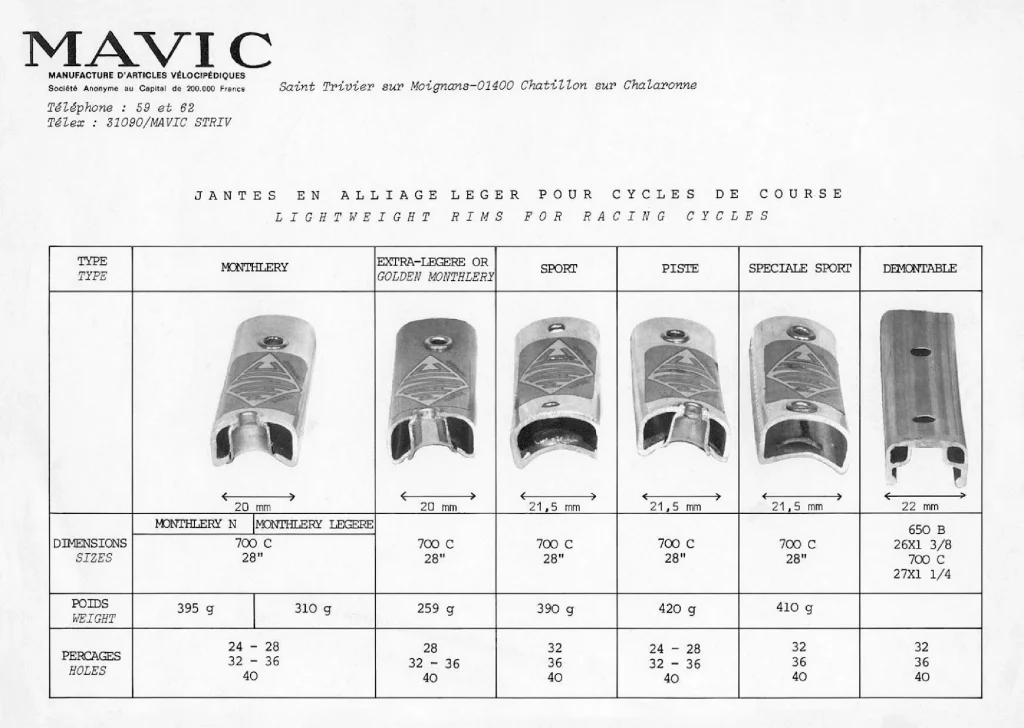

For collectors of vintage steel, the mid-80s represented a peak for traditional rim design. In late 1985, Mavic introduced the legendary MA, MA2 and MA40 models for the 1986 model year. Each of these models featured a slightly wider 20.5 mm width compared to the 19.8 mm of their predecessor, the Module E. This increased their lateral rigidity and structural strength while providing a wider base that improved traction and enabled high-pressure clinchers to be used more reliably.

Mavic’s spirit of innovation occasionally soared beyond the road. In 1984, the company created the Mavic Air Department to market ultra-light aircraft (ULM) such as the French-designed Air Plume and the American Avid Flyer. These were sold as kits or fully assembled, but sales were minimal. The tragic death of Bruno Gormand in a car accident in December 1985 put an end to this venture, though the company’s Cessna aircraft continued to provide vital radio relays for professional races until 1986.

Following the tragic loss of Gormand, his widow Madame Cecile Gormand took the helm as President, guiding Mavic with the same characteristic enthusiasm that had defined the family’s nearly 70 year stewardship. The dawn of the 1990s signaled a major turning point for the brand’s corporate structure, however.

On November 30, 1990, Madame Gormand agreed to a management buyout (MBO), passing control of the company to four key members of the executive staff and an outside financial partner, which led to the formation of a new holding company. This transition marked the end of an era of direct Gormand ownership that then instigated a decade of significant corporate shifts.

It also marked the beginning of an era of innovative product design and rapid technological advancement at Mavic. Both of these were accelerated when the sports giant Salomon purchased Mavic in 1994 and brought its significant wherewithal to the partnership. And then this happened again when Adidas merged with Salomon in 1998 to become the world’s second-largest sporting goods company.

By the end of the 1980s, Mavic had already begun to shift its focus away from individual components and toward a “global system” approach. This philosophy—that a wheel should be designed as a complete unit consisting of hub, spokes and rim—led to 1990s breakthroughs like the Cosmic (1994) and ultra-light Helium (1996) wheelsets. While competitors like Roval had experimented with this approach before, Mavic’s scale had the sufficiency to make pre-built wheelsets the industry standard. This was despite initial resistance from bike shops everywhere that relied on the labor associated with building and maintaining hand-built wheels to keep ringing the register.

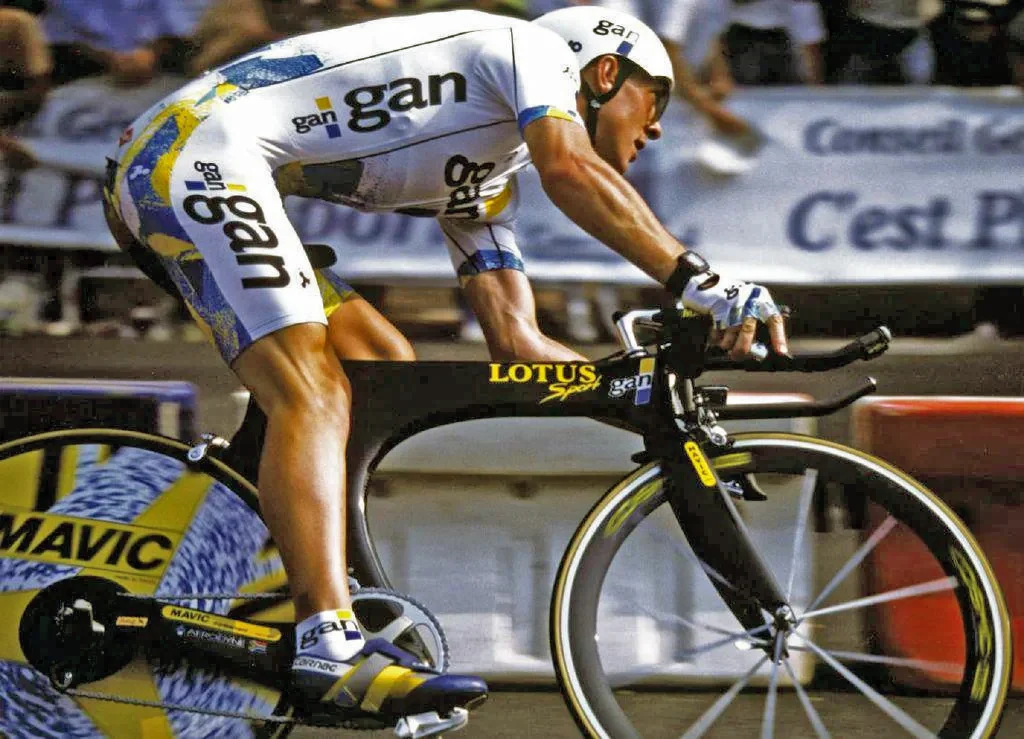

Mavic also made an early foray into electronic shifting around that time, namely with the Zap Mavic System (ZMS), which produced some of the professional peloton’s most harrowing stories of the day. During the 1993 Tour de France, Tony Rominger ignored his director’s warnings and used the ZMS in a critical time trial stage. The system failed just 3km into the course, locking him into a massive 54/12 gear for his remaining ride. Miraculously, Rominger still won the stage on the flat course, though the incident highlighted the system’s early instability.

In another Mavic electronic shifting mishap, Chris Boardman’s mechanic failed to tighten a battery cap during a race, causing the spring-loaded battery pack to launch from the handlebars into the crowd. What a great souvenir that must have made for some lucky cycling fan! Boardman also experienced “ghost shifting” during his famous prologue win in the 1994 edition of the Tour de France, when he was reportedly intimidated by the system because his gears began moving on their own before the race even started.

Ultimately, Mavic’s first century was not merely a sequence of patents and podiums, but a living example of the French engineering spirit that transformed the bicycle from a simple velocipede into a precision racing instrument. From the secret “wood-painted” alloy rims of the 1930s to the aero-disc revolution that secured an eight-second victory in 1989, the company proved that reliability and speed were never mutually exclusive.

As the brand returns to its roots as an agile, family-run firm, we look back at these golden decades with a profound appreciation for the yellow diamond – a symbol that continues to represent strength, passion and victory, on the professional podium or upon arriving at your local destination. For the vintage connoisseur, Mavic’s legacy represents a standard of excellence and commitment to quality few other component manufacturers can equal in significance or time. For that, we should all be thankful.

The 21st century has tested the yellow diamond as never before, leading the company through a turbulent chapter of corporate uncertainty. In 2019, Amer Sports divested the brand to a U.S.-based private equity firm. The following year, administrative murkiness would reveal that an obscure Delaware entity named M Sports International LLC was the actual suitor. This confusion reached a fever pitch by May 2020, when Mavic was placed under judicial review by the Commercial Court of Grenoble as creditors voiced concerns about the company’s viability. Fortunately, the Bourrelier Group stepped in that July, creating a corporate structure that secured the survival of the Saint-Trivier factory and the Annecy headquarters, effectively returning Mavic to its roots as an agile, family-run French SME.

Under Bourrelier’s stewardship, Mavic has reclaimed its equilibrium, celebrating its 134th anniversary in 2023 with a grand retrospective in Annecy. While the iconic yellow cars were sadly replaced by Shimano in the Tour de France peloton in 2022—ending nearly five decades of roadside salvation—the brand’s heart continues to beat strongly in France.

Today, Mavic employs approximately 200 dedicated craftspeople who together carry the torch, producing high-performance carbon and aluminum wheels (and many other products) that grace the bikes (and bodies) of professional and amateur riders across the globe. From the secret alloy tests of the Dura rim to the digital pioneering of the Zap and Mektronic groups, Mavic remains a paragon of resilience and ingenuity, forever linked to the sport of cycling and our shared understanding of what works best when you really need it.

https://www.mavic.com/en-us/c/history

https://road.cc/content/feature/118858-125-years-mavic-ride-through-cycling-history

https://uk.fashionnetwork.com/news/Amer-sports-completes-sale-of-mavic,1118367.html

https://rouesveloexpert.com/mavic-histoire/

https://www.velomotion.net/2022/09/mavic-wheels-carbon-history-production/

https://www.smontanaro.net/CR/2009/03/00250

https://www.theproscloset.com/blogs/news/the-mavic-story-130-years-of-cycling-innovation

http://velo-retro.com/mtline.html

https://www.biketo.com/industry/34575.html