About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

Many years ago, I was strolling through a garage sale early one Saturday morning when I stumbled upon a pile of vintage lightweight bike framesets and parts. There were quite a few nice finds in the mix: A minty fresh Peugeot PX-10, a Carlton with Reynolds 531 tubing, and a newer Raleigh frame and fork. There was one frameset that really caught my attention, though.

It was a Bianchi that looked to be from the early 1980s — with clean lug work, horizontal dropouts, “Bianchi” stamped on the seat stay caps, no brakes or braze-ons for fenders or rear rack — all of which led me to believe the frameset was an early Italian track model. The paint had previously been a rich blueish-green color but was now chipped and oxidized throughout. The frame and fork both needed to be stripped and resprayed, for starters. On its head tube, the frame still had a faint Columbus stamp engraved into it. Quality materials that accompanied a quality build.

“What a choice find,” I quietly thought to myself, as I happened to be in the market for a frameset to build up as a single speed or fixie. If ever there were a frameset perfect for that use, this vintage Bianchi made with comfortable, trusty Columbus tubing was sure to be it. As if it couldn’t get any better, when I presented the blue/green/orange/red mass to the garage sale proprietor, he said, “Oh, that wicked old thing, hell, you can have it!” It felt like a really good omen, or as they say in Milano, “molto auspicio.”

Bellissimo! Ciao! I sprinted home in a fury to scour the Internet and find out exactly what I had stumbled upon. In my quest for info on the garage sale score of the decade, an abundance of info flourished before my eyes regarding the legend of Edoardo Bianchi himself and his humble bike shop beginnings way back in 1885. Unfortunately, I didn’t uncover much information on my newly acquired frame, but the wealth of history I learned about Edoardo Bianchi the man and the enduring company he started were far more interesting than the nebulous specs of an old track frameset.

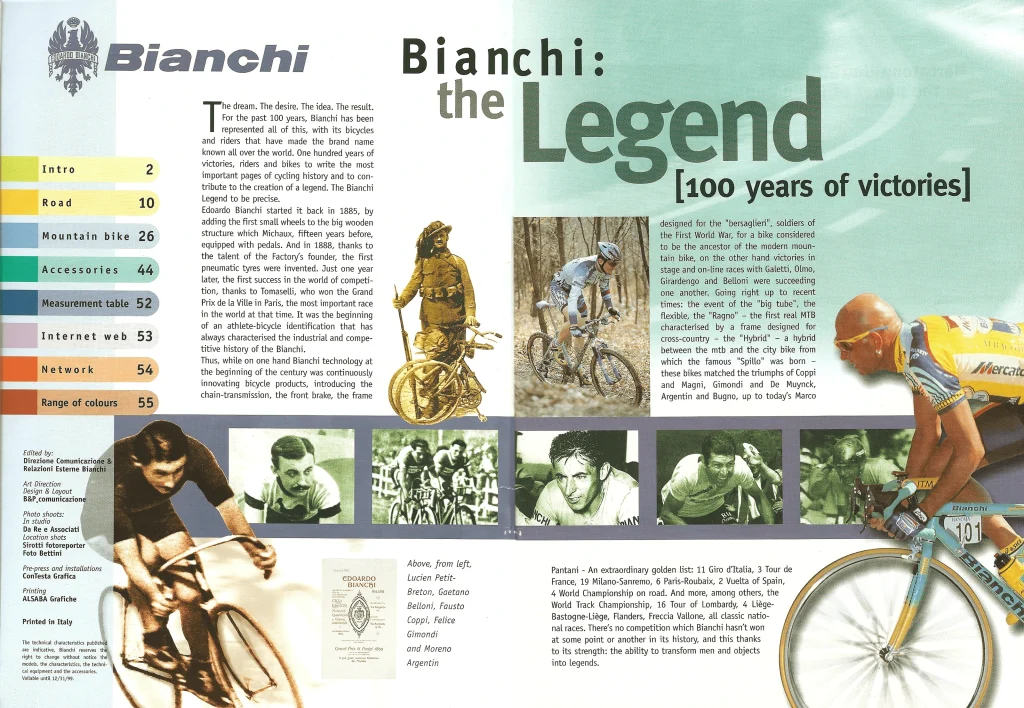

Much like Henry Ford was to the modern automobile, Edoardo Bianchi was to the modern bicycle. His business and manufacturing innovations coupled uniquely well with the technical contributions provided by his company’s “Reparto Corse,” securing Bianchi’s place on the podium as one of the most influential manufacturers in bike racing history and cycling at large. The company’s success even led them to dabble in automobiles, albeit for a brief moment in time in a highly localized market. Perhaps this persistence is why Bianchi remains the oldest continuously operating bicycle manufacturer in the world.

Edoardo Bianchi had a difficult but also supportive childhood. He was born on July 17, 1865 in Milan, Italy, the same time and place that the country’s first major department store was opened with great fanfare by the Bocconi brothers. At just seven years old, Edoardo entered Martinitt, a historical boys orphanage in central Milan that was established in the 16th Century by worshipers of Saint Martin, as the orphanage was originally based in the eponymous oratory. There, a young Bianchi learned basic mechanics and began developing his passion for mechanical engineering.

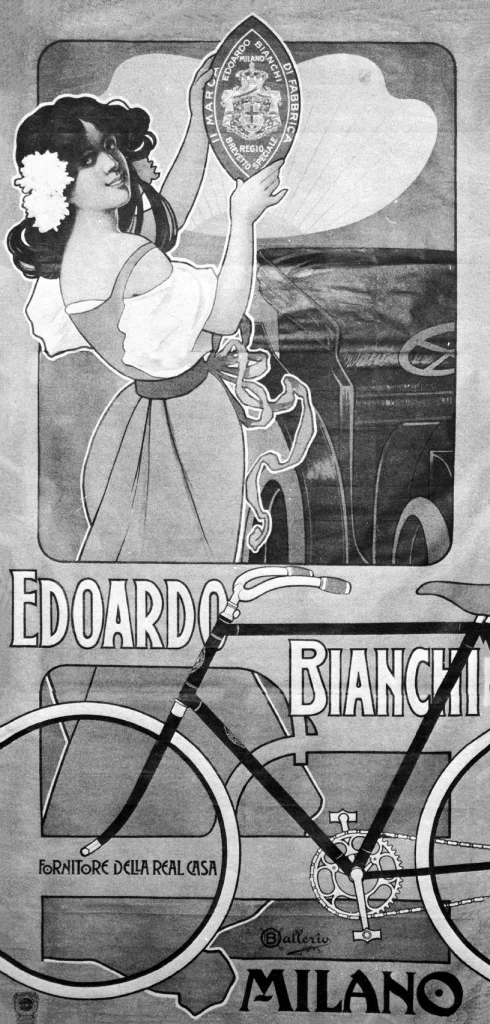

High wheel (or penny-farthing) bicycles had only just been invented in 1885. That didn’t stop a faithful, youthful 21 year old Edoardo Bianchi from establishing his first bike shop that year on Milan’s then-bustling Via Nirone. It was quickly revealed that Bianchi was a visionary because within three short years after opening, his company introduced one of the first bikes with wheels of nearly identical size and a chain drive — called the “safety bicycle” — as well as the world’s first production bike with Dunlop inner tubes and pneumatic tires. (Asses worldwide must have sighed in collective relief!)

And that was just the beginning of his company’s meteoric rise. Within ten years of Bianchi’s fateful opening of his little bike repair shop, Edoardo’s company was awarded the prestigious opportunity to build a custom bike for Italian royalty when it was invited to court at the Villa Reale in Monza in 1895. The lucky beneficiary of this special bicycle was to be none other than Queen Margherita of Savoy herself. To accommodate the queen’s wide skirts, Bianchi modified the frame’s geometry before teaching the queen how to ride her new machine in picturesque Monza Park. The resulting endorsement of Bianchi by Margherita’s “Royal Crown” had an undeniably positive impact on Edoardo’s business and reputation.

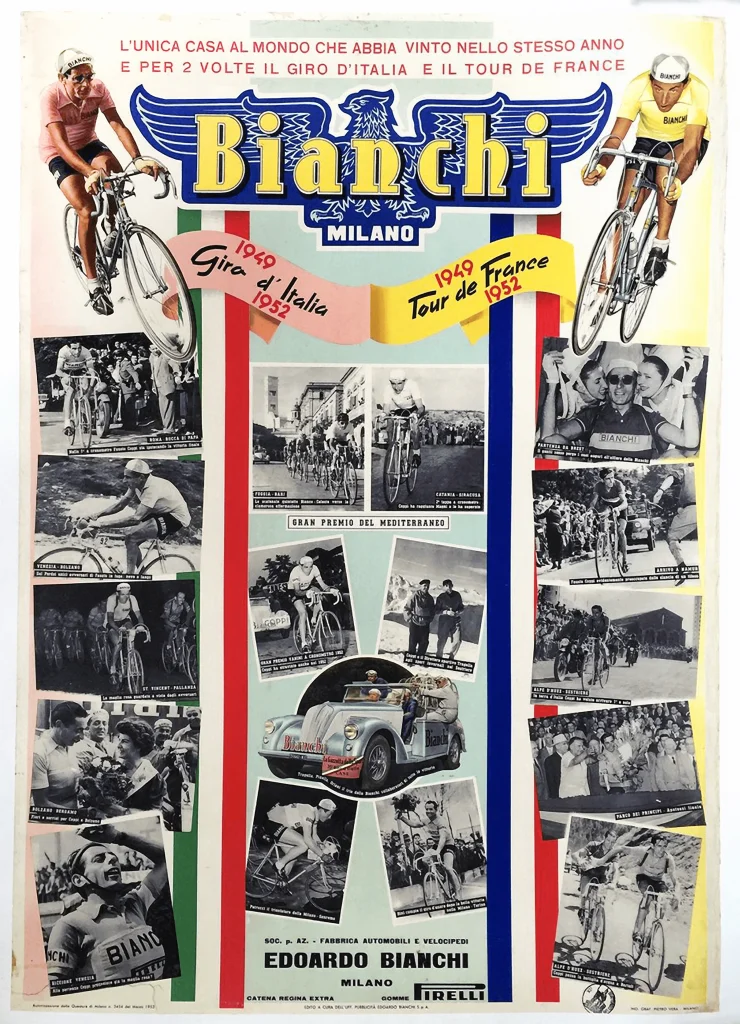

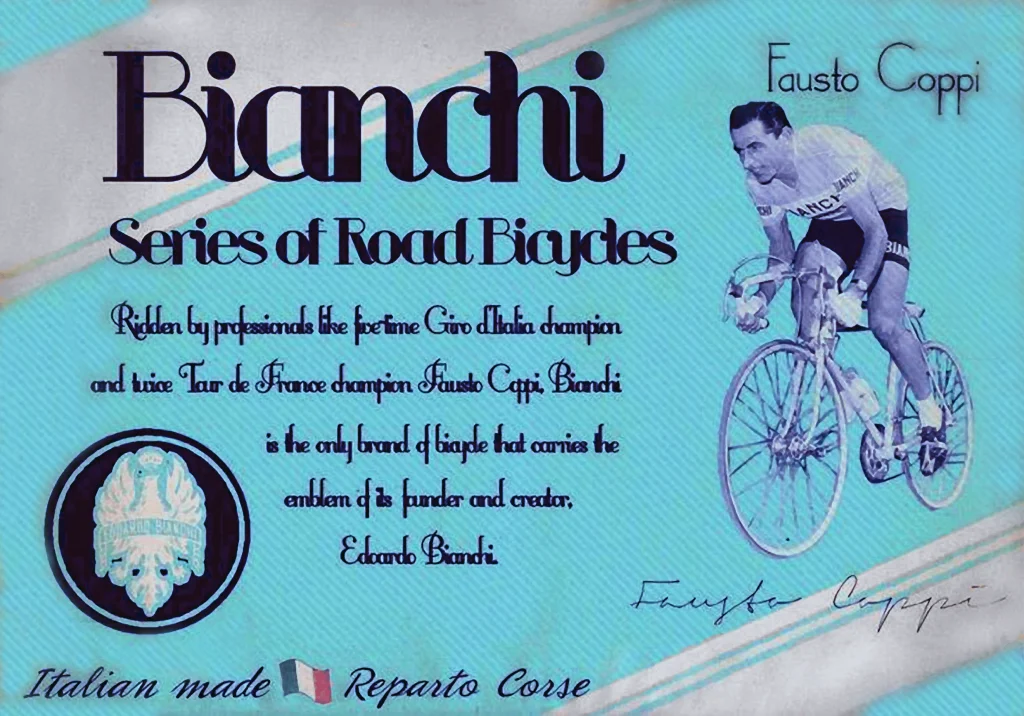

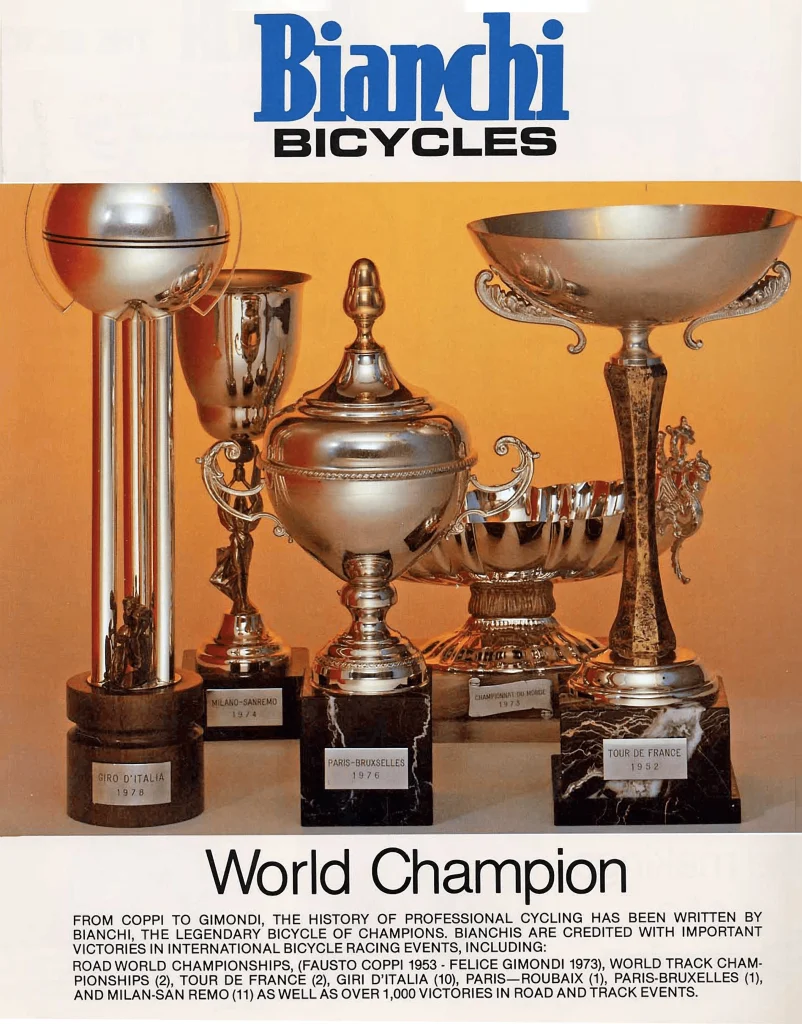

Reparto Corse — or racing department, literally — was yet another brainchild of Edoardo himself in the late 19th century. In today’s world of Italian automotive, motorcycle and bicycle racing, Reparto Corse is a universal term which represents the utmost in technological innovation for the purpose of winning races. Bianchi first coined the term and put it to work in 1896 by using bike races as proving grounds for advancing his company’s nascent technologies. Through present, these efforts have yielded 12 Giros d’Italia, three Tours de France, three Vueltas de España, five World Championship victories and a single hour record back in 1942, among other celeste-colored palmarès.

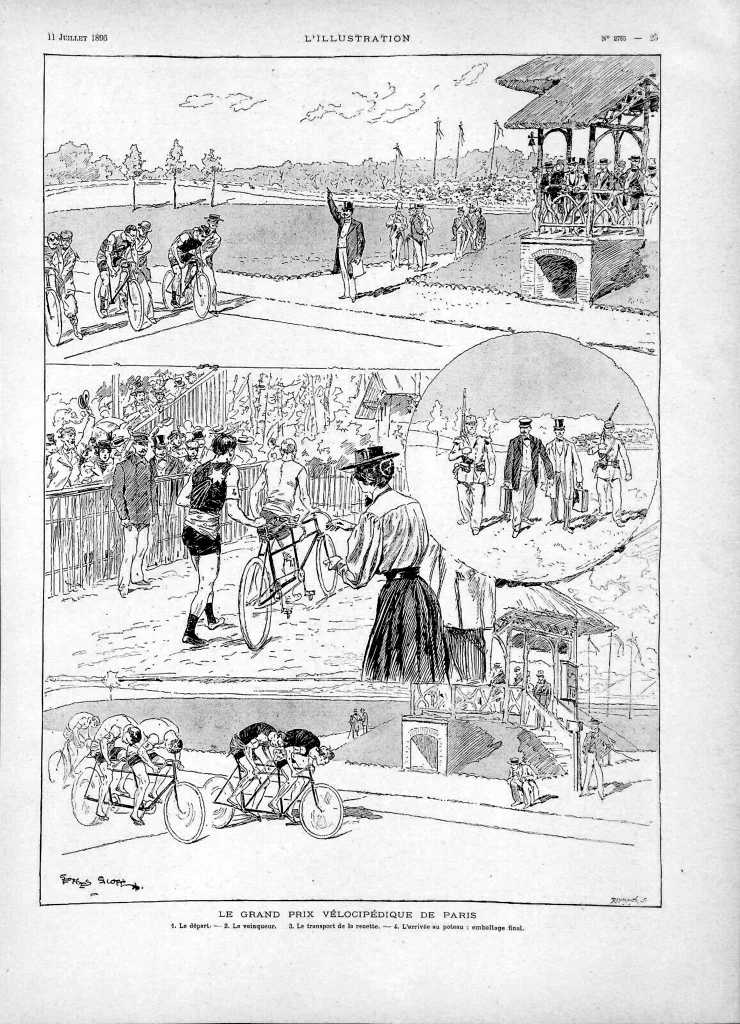

By 1899, a Bianchi ridden by Giovanni Tommaselli rolled to victory in the Grand Prix of Paris, the predecessor to the Tour De France and preeminent velocipede race of the day. The notoriety Bianchi was receiving from podium placements and its Reparto Corse integration efforts made the company one of the most popular brands in the cycling industry. Growth was exponential during the early 20th Century as Bianchi became the top choice for competitive bicycle racers across Europe.

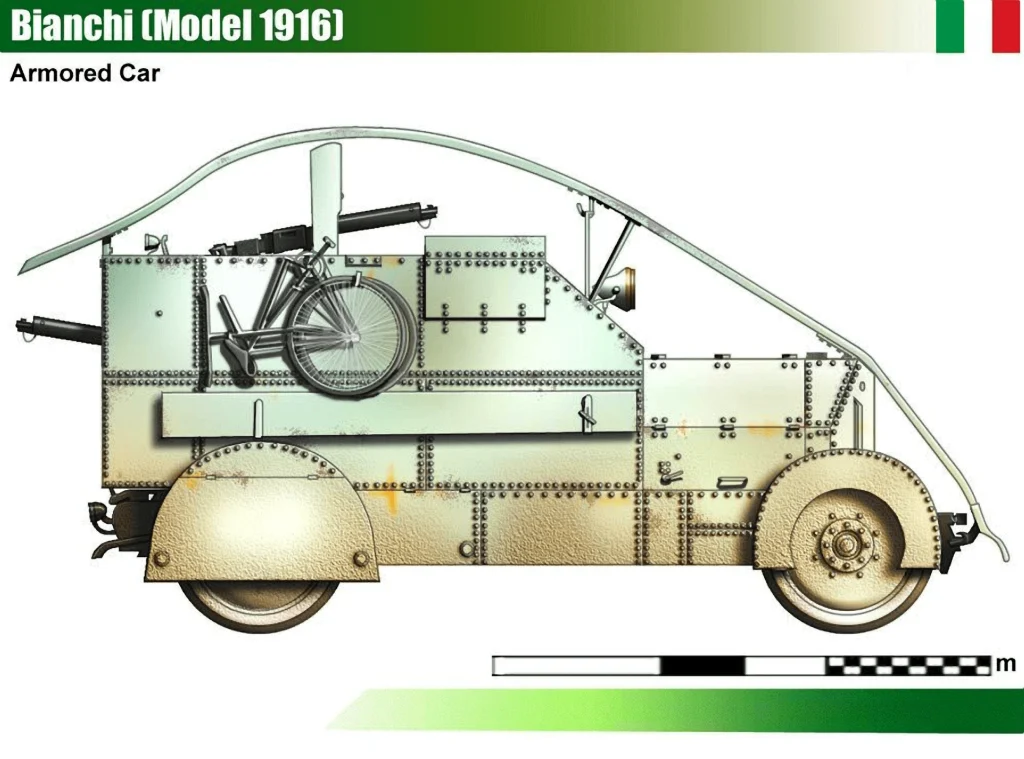

Just as E. Bianchi & C. — now greatly expanded across Via Nino Bixia and Via Paolo Frisi — started enjoying the spoils of being the leading manufacturer of high-performance bicycles, World War I interrupted the company’s trajectory in the ugliest of ways. Because of Bianchi’s size and influence, the Italian government mandated the company focus all its efforts on supporting the war. Bianchi had become more than just a bike manufacturer by this point. Company documents from 1914 detail its production of 45,000 bicycles, 1,500 motorcycles and even 1,000 cars that year.

Sweet little cars that evolved from something like tractors with bicycle wheels, fenders and sofa seats mounted to 2.25 horsepower De Dion-Bouton engines in 1900, only to become heavily armored cars built to withstand munitions and kill people a short but tumultuous 15 years later.

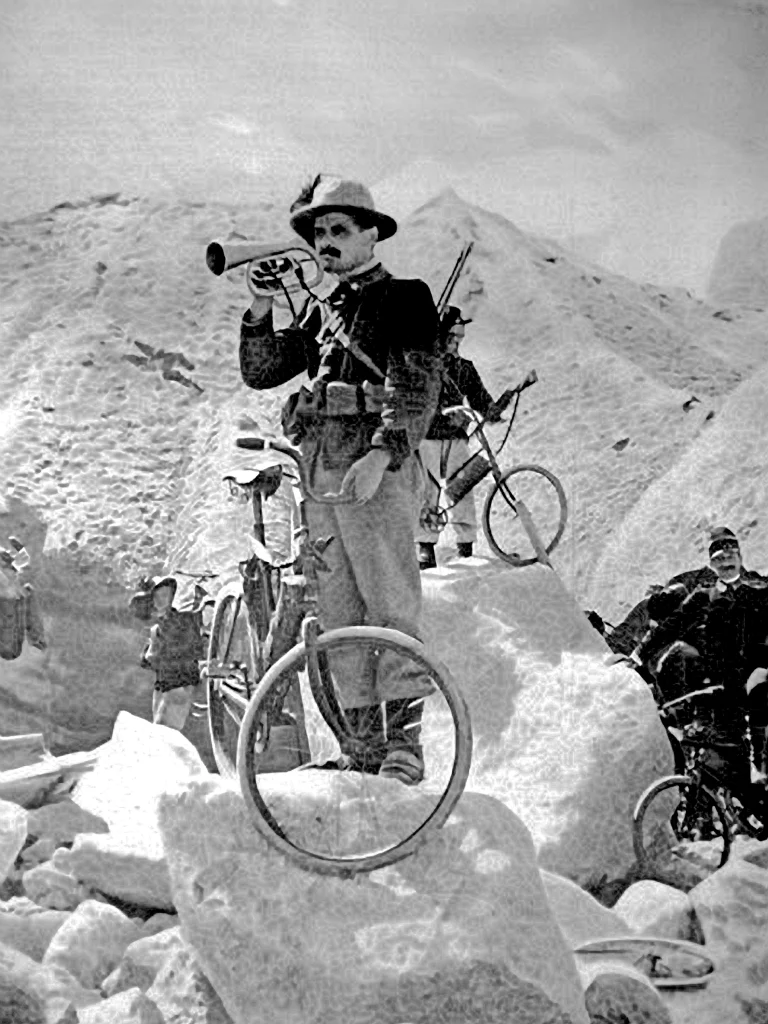

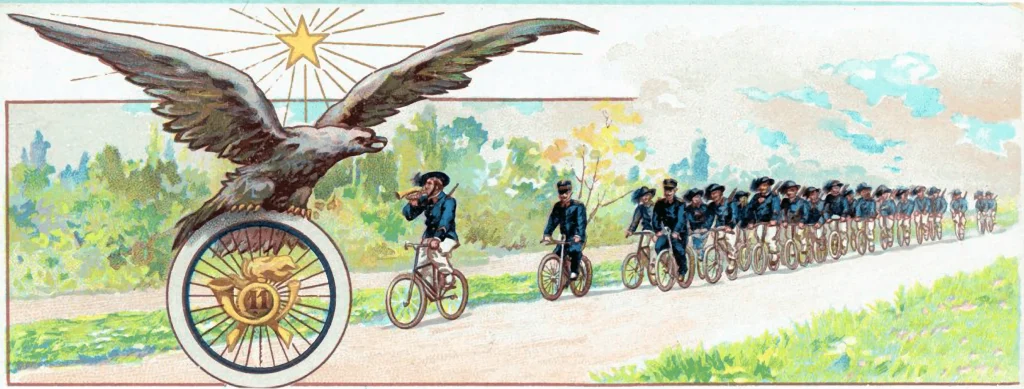

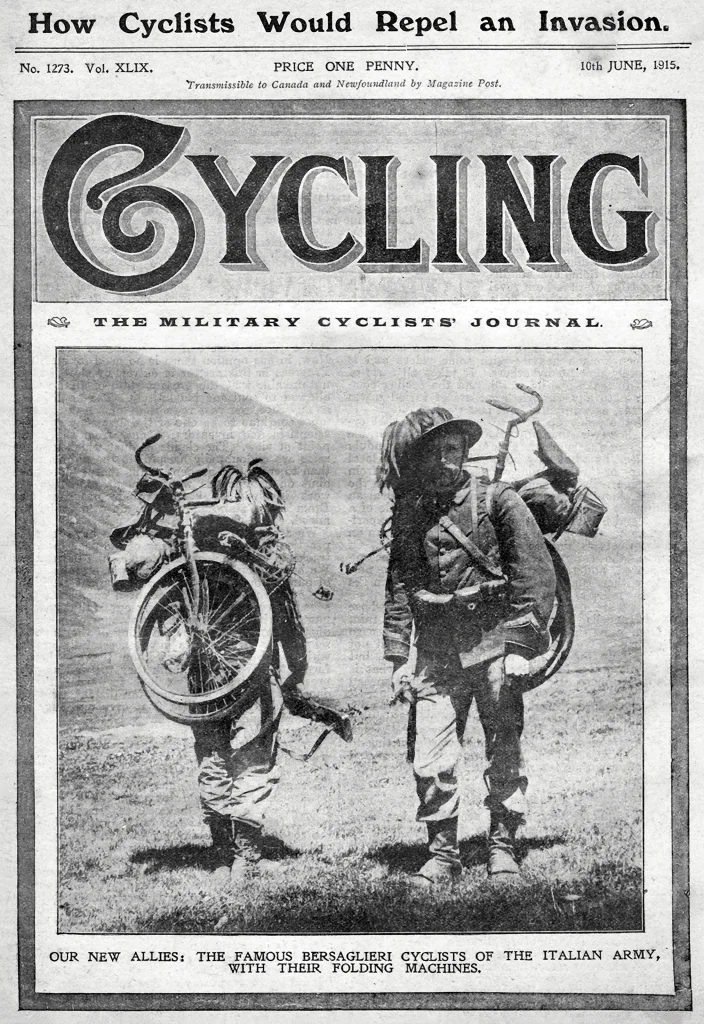

Given the national effort to mobilize all available resources in support of fighting the war, it was clear why the Italian government chose to harness Bianchi’s resourcefulness and depth of manufacturing. The most notable bike-related invention stemming from the 1914-1918 wartime effort was the birth of the “bersaglieri” bicycle, which were durable machines made for sharpshooting infantrymen who rode long, rocky distances on what could rightfully be considered the first mountain bikes.

A half-century before Joe Breeze, Tom Ritchey and Gary Fisher bombed the downhills of Mount Tamalpais in Northern California’s lovely Marin county, Bianchi had already developed and refined an advanced all-terrain bicycle for the Italian army.

That bicycle, of which there were several variations, featured front and rear spring suspension systems, telescoping seat stays, 60cm wheels with wide Pirelli pneumatic tires, a frame that could break down and transport like a backpack, and then the requisite weapons integrations.

These weapons integrations included a flip-top saddle that revealed a mount for heavy artillery and a mount for attaching an adjoining support arm from the bike’s top tube/seat tube cluster to an infantryman’s forefoot. What a historically anomalous — even perverse — use of such a fine, peaceful machine, our beautiful bicycle.

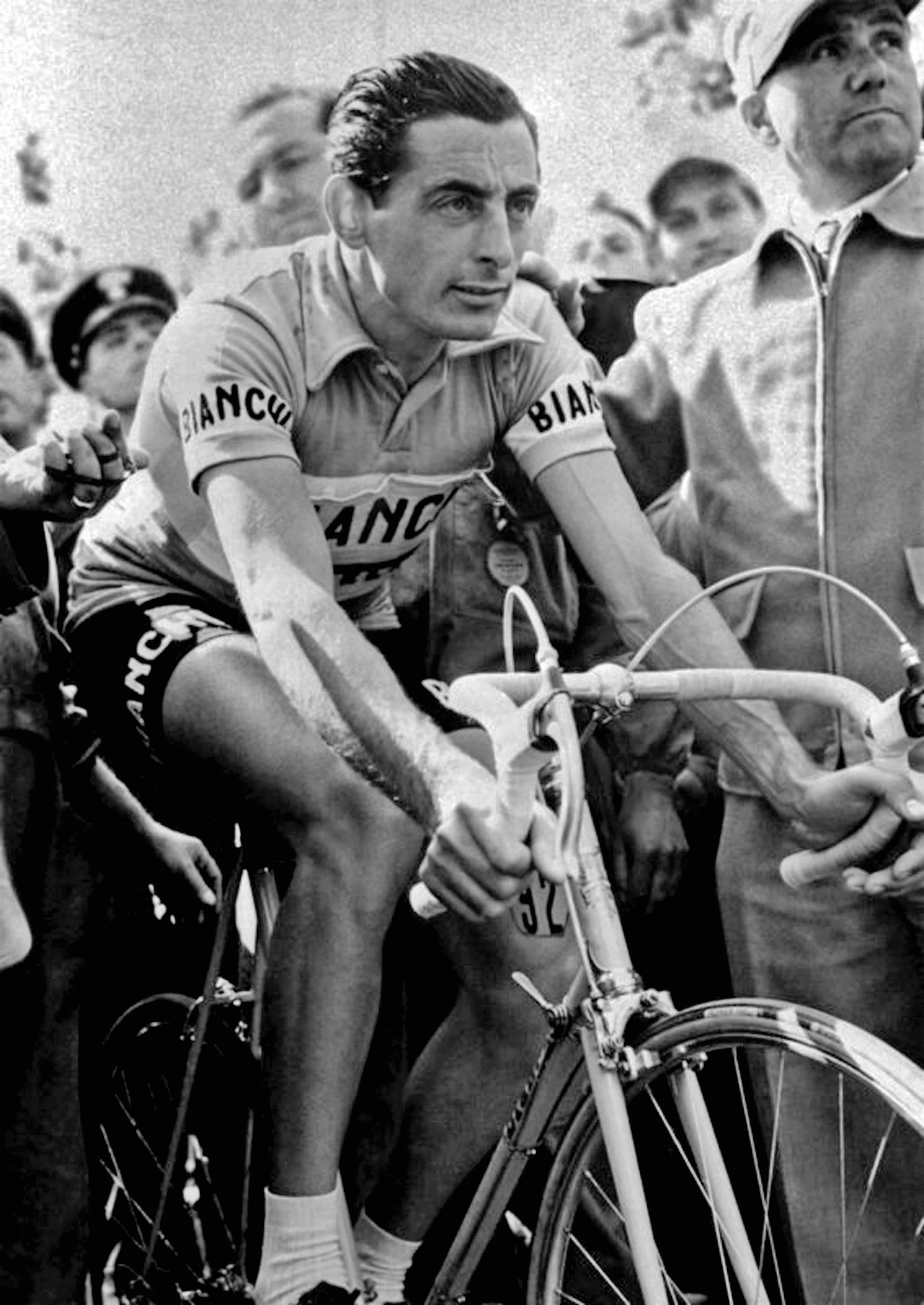

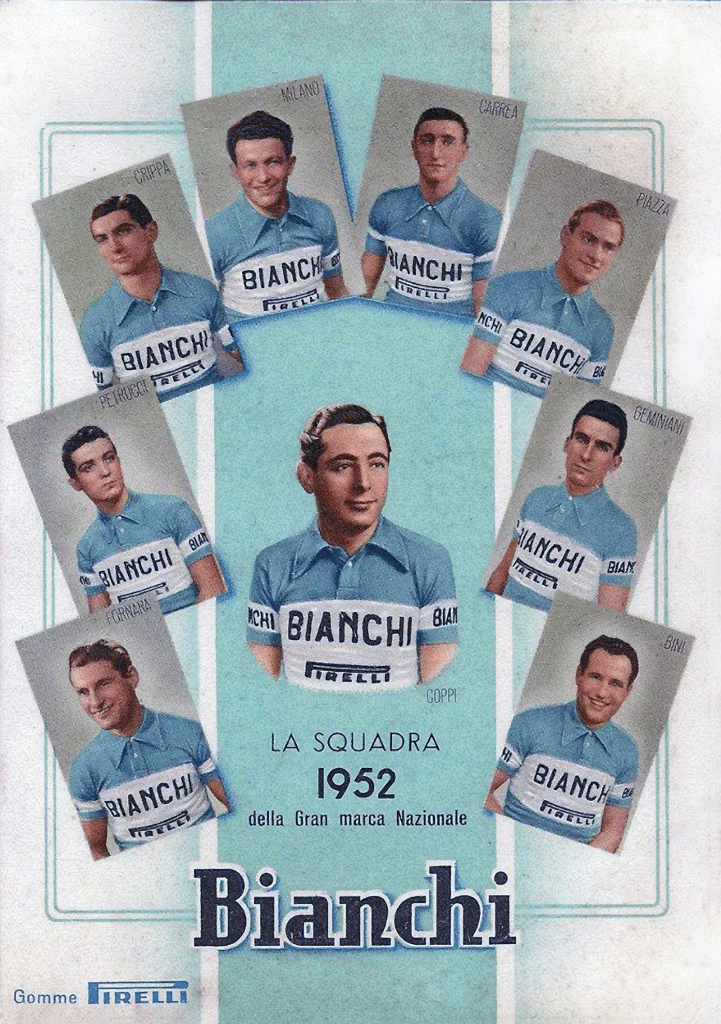

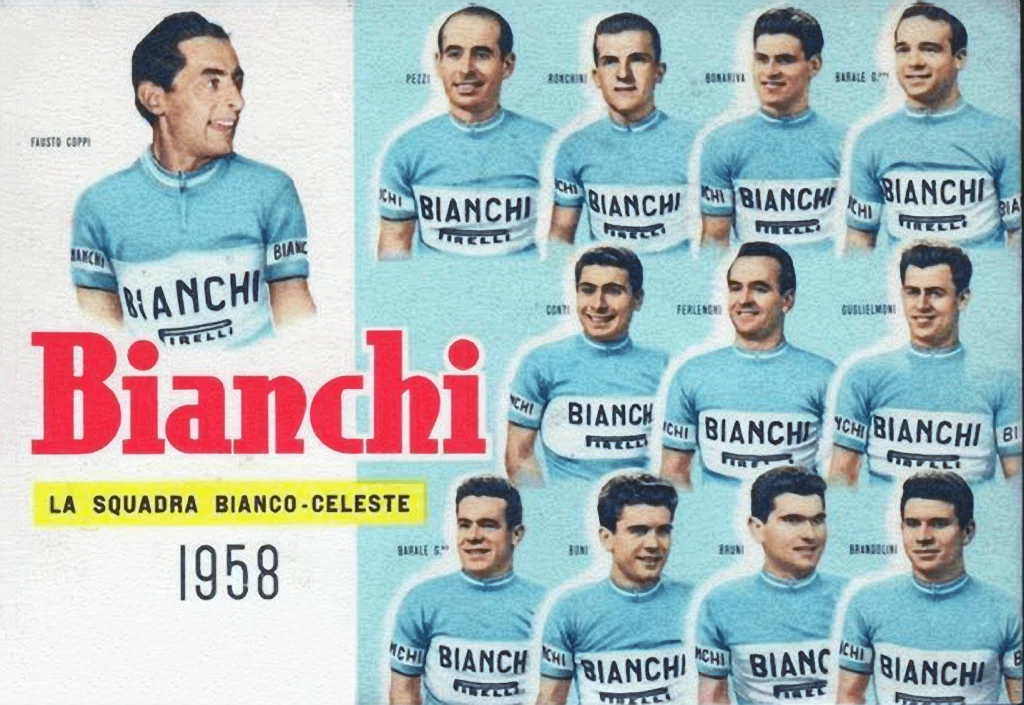

After a relatively successful 1920s and 1930s with various wins in the Giro d’Italia and other races of repute that drove company bicycle sales to 70,000 units by 1935, the 1940s was an even more significant decade for Bianchi. The incomparable Fausto Coppi started racing for the company, the destruction of Bianchi’s manufacturing facilities in WWII bombings halted bicycle production for three arduous years and Bianchi’s most recognizable trademark — the bluish-green paint color “celeste” — was introduced to widespread acclaim.

There are several stories behind how “Bianchi blue” came about, but nobody has firmly documented the truthful origin story behind this lovely color. Romantics say Edoardo himself created the color in honor of Queen Margherita’s beautiful eyes. Naturalists claim it was Edoardo’s homage to Milan and its beautiful sky, or “celeste.” A third story was that Bianchi had so much surplus green paint from Mussolini’s WWII reign that they mixed it with blue to create a unique color unassociated with the war or its endless atrocities.

Still another origin story was that celeste was a paint mixing mistake that somehow ended up on team bikes only days before the Giro d’Italia. Fausto Coppi and his teammates thought the bikes were purposely painted that way for good luck and the rest is (or may be) history. According to bike design legend and former Bianchi USA employee, Sky Yeager, none of these stories are responsible for the creation of celeste. According to her interview with the imminently well-informed Nels Cone, Edoardo created it to be a unique standout in the peloton and the color evolved naturally over the years through a few different variations. Who knows?

What is certain is that Fausto Coppi won five Giros d’Italia and two Tours de France with the support of his celeste Bianchi and its Reparto Corse lifeblood. Then WWII not only interrupted Bianchi’s business, but also the career of Coppi. The “Campionissimo” won his first Giro in 1940 and set the world hour record in 1942. After a three year hiatus from racing due to the war, he went on to achieve his greatest accomplishments by pulling an exceptionally rare “double double” — winning both the Giro and Tour in the same year, twice — as he did first in 1949 and then again in 1952.

In 1953, Coppi won the World Championships aboard a Bianchi that had an integrated headset — an innovation many decades ahead of its time. The only racer in history with more impressive palmarès than Coppi is The Cannibal himself, Eddy Merckx. Had it not been for the interruption of WWII, Coppi may well have even superseded the historic achievements of Merckx.

Were the destruction of the Bianchi manufacturing facility during WWII not tragic enough, tragedy struck the company on multiple fronts during the 1940s and 1950s. Edoardo died after a horrible car accident in the city of Varese in 1946. Fausto Coppi’s beloved younger brother, Serse, died in a sprint finish at the 1951 Giro del Piemonte. Then Fausto contracted malaria that was initially misdiagnosed as a bronchial infection after riding in an exhibition event in Burkina Faso, Africa and he also died in January 1960 at the young age of 40.

Leadership in Bianchi passed to Edoardo’s son, Giuseppe, and his restructuring of the company nearly brought it to its knees. After the Italian government paid its post-war financial debts to Bianchi, the company survived the 1950s relatively intact only to cease production of its automobiles and motorcycles in the 1960s to become a dedicated bicycle manufacturer once again.

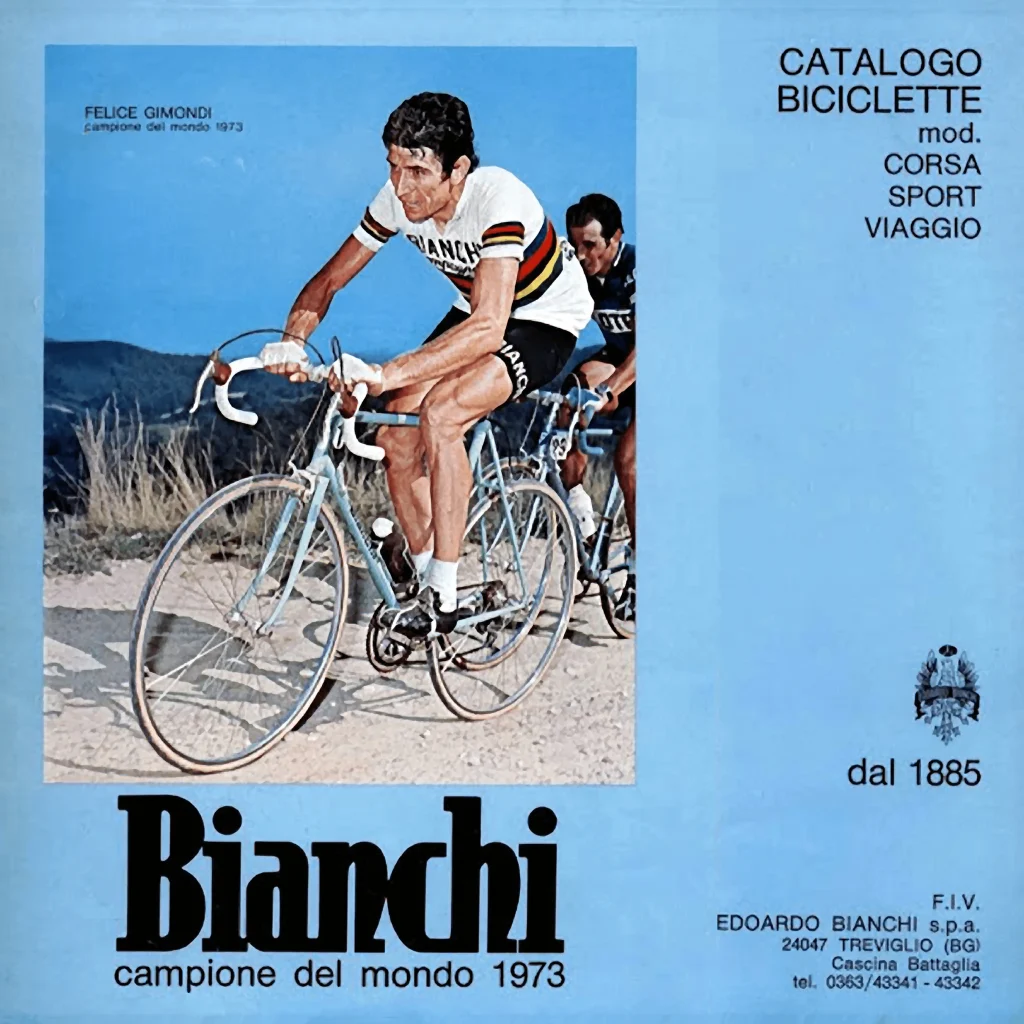

After the untimely death of Fausto Coppi, the 1960s witnessed the rise of another cycling legend aboard a celeste Bianchi, Felice Gimondi. With three Giro victories, a Tour victory in his first year as a professional and a win in the Vuelta a España, Gimondi brought more fame and visibility to the Bianchi brand and its Reparto Corse skunkworks.

During the heydays of Coppi and Gimondi, the celeste color that Bianchi trademarked became synonymous with victory. It helped carry Bianchi through the 1970s and 1980s. As the nature of the cycling industry changed and manufacturing costs became less expensive overseas, Bianchi started mass producing less expensive frames in Japan in the late 1980s. Although some scoffed at the fact a Japanese made Bianchi was not true Italian, the quality and craftsmanship of Japanese Bianchis were actually superior to many Italian models. The number of podium finishes aboard Bianchi bicycles in that era would seem to support this observation.

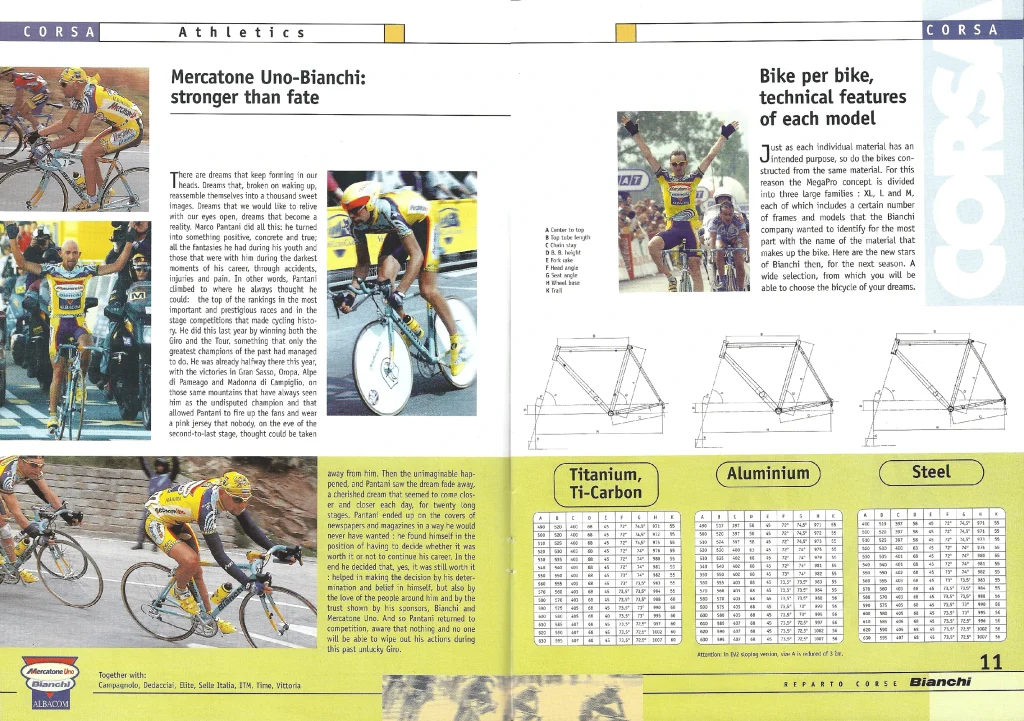

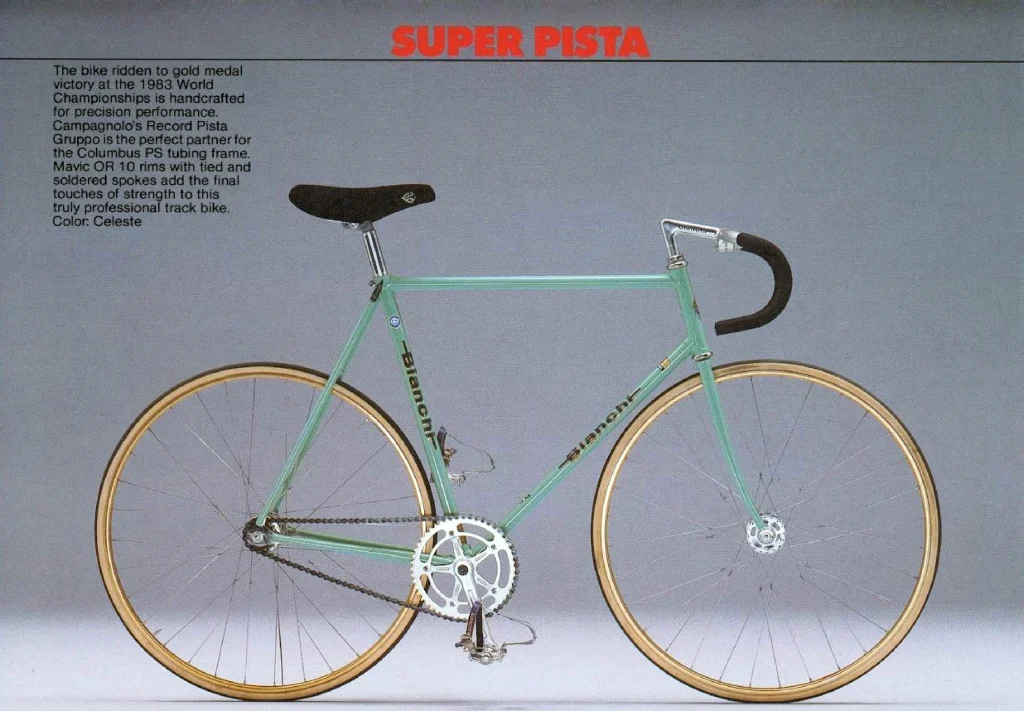

Bianchi had long perfected the art of lugged steel frame construction built with Columbus tubing by the 1980s. Models such as the Specialissima and Centenario were especially in demand with their gorgeous chromed lugs and celeste paint. One bike of particular rarity is the Specialissima X4 Argentin, which was the flagship bike for Bianchi in 1988. Built with Columbus SLX tubing, celeste paint, black chroming, custom engraving all over (including an X4 on the rear brake bridge), and equipped with Campy C-Record, this model was never offered in any domestic U.S. catalog. It was also during this time in the late 1980s that the Reparto Corse started experimenting with new frame materials such as carbon, aluminum and titanium.

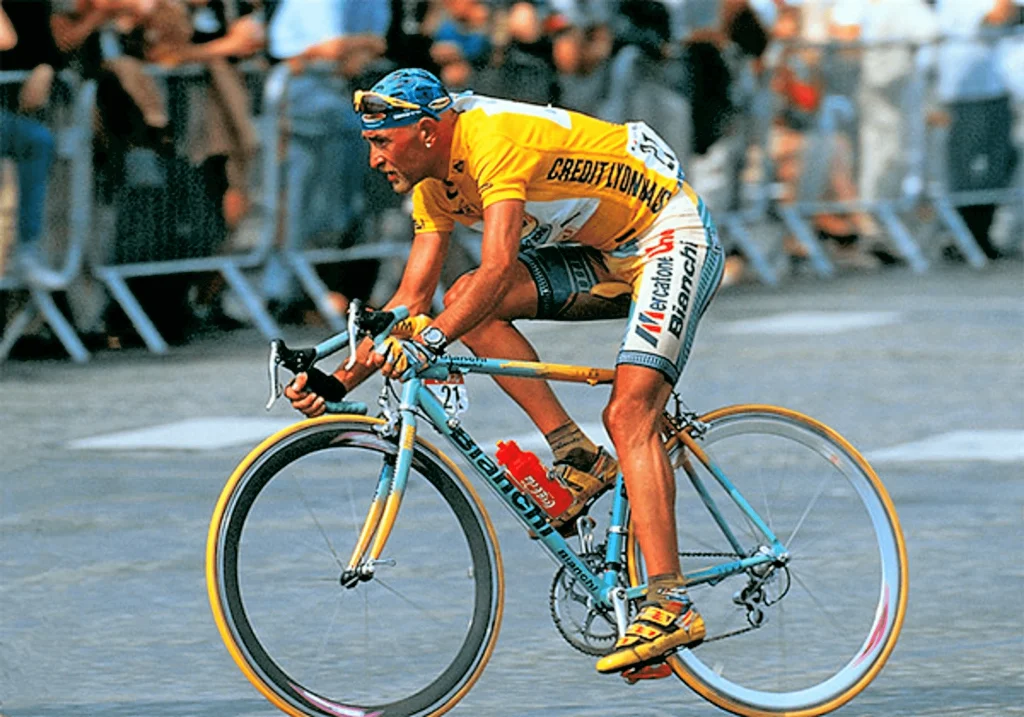

With aluminum, the Reparto Corse developed their EV4 tubing, which pushed the limits of lightweight and stiffness. A 1.9 lb EV4-tubed Bianchi was ridden in the 2000 Olympics by none other than “Il Pirata” — the late, great Marco Pantani. The EV series frames also featured patented structural foam injection for added strength and durability. Other innovations like MegaPro tubing, which vary the diameter and tapering of tubes for added shock absorption and rigidity, sloping top tubes for light weight and torsional stiffness, and the return of integrated headsets make a modern aluminum Bianchi more race worthy than most all of its competitors.

Along with aluminum, Bianchi utilizes aerospace grade titanium and carbon to produce frames and components which are found on many of the Reparto Corse labeled Bianchis. Only eight years prior to Pantani’s EV4 Bianchi, Gianni Bugno won the 1992 Worlds on a bike that weighed more than four pounds more than Il Pirate’s ultra-lightweight specimen, further proving the worth of Bianchi’s Reparto Corse in the 1990s and its continued influence on the advancement of bicycle technology.

The 21st century ushered in Team Bianchi for the 2000-2003 pro cycling seasons, which had been cobbled together from the remnants of the Coast team before it. Team Bianchi was probably best known for its now-disgraced star rider, Jan Ullrich. Despite its short-lived foray back into title sponsorship of pro cycling teams, Bianchi has continued to improve the bikes it makes since the early 2000s through today.

Other manufacturers who can’t clock but half the 135 years Bianchi can clock have either sold out or gone the route of mass production and recreational homogeneity. Bianchi’s proud Reparto Corse roots keep the company firmly planted in its brand values and racing heritage — then as now, which is why the company’s advanced bicycles are featured in 2020 UCI WorldTour events globally, including the Triple Crown of bike racing: the Giro d’Italia, Tour de France and Vuelta a España.

After a month of collecting parts and finishing the rattlecan paint job on my free Bianchi track frame, it was ready to race. The paint was a celeste knock off — a pastel blueish-green hue found at Home Depot which was a bit darker than the familiar celeste color, but close enough to pass the 10′ test. The finished product looked gorgeous and with some vintage decals and parts that included Campy Pista cranks, a Campy Pista wheelset, and Cinelli bar and stem combination, my impostor celeste Bianchi turned a lot of heads everywhere we went together.

Since becoming accustomed to racing a Specialized S-works track bike, the feel and performance of the lugged Columbus steel frameset was a welcome change. After transitioning to all the newest carbon tech out there, I had forgotten about the superior ride quality of traditional steel, not to mention the pride in owning such a unique rig that garnered compliments from all of my fixie and road cronies. Steel is indeed real, and so is the Reparto Corse — however you manage to get their support. Bellissimo! Ciao!

Related Ebykr Articles:

Bianchi Bicycles Image Gallery

The Eagle and the Bianchi Bicycle

Tech Specs: 1959 Bianchi Campione del Mondo

Tech Specs: 1964 Bianchi Specialissima

Ebykr Bianchi Article Sources:

Cycling Utah – “Classic Corner” Article on Bianchi by Greg Overton

MuseoNicolos – Article on Bianchi Bicycles

Premium Cycling – Vintage & Collectible Bicycles

Icon Wheels Magazine – Article on Edoardo Bianchi by Marco Coletto

[…] vintage bicycle enthusiasts. While not as appealing or recognizable as Bianchi’s bluish-green celeste color, Legnano’s “verde transparente” color still manages to capture that brand’s […]

[…] articles on Benotto and Gios bicycles, I won’t recount the history of Bianchi here, but this informative article by Kurt Gensheimer is a great place to start, as is their Wikipedia […]

Thanks for the “imminently well-informed” accolade, lol

[…] a central band on which Edoardo Bianchi’s full name was inscribed from 1901. As providers of groundbreaking bicycles to the royal household, the Savoy coat-of-arms was subsequently added in […]

[…] Reparto Corse: Edoardo Bianchi & the History of Bianchi Bicycles […]

[…] for the domestic market. Eight years later in 2000, a Swedish company bought both Cycleurope and Bianchi, and assigned Bianchi the continuing role of making race […]

[…] (and no doubt profitable), the racing world promoted an emerging rivalry between the Legnano and Bianchi teams, the latter being a far older company established in 1885, who must have seen Legnano as […]

Just purchased a new 928 Carbon and was interested in what the reparto corse decaling meant and came across your fabulous history of Bianchi.

Makes me very proud to ride a machine with such a rich history and a stand out in so much mass produced equipment these days.

Many thanks!

It’s amazing what you can find in someones junk pile. Truly a nice find and project.

Eric

Thanks for such an interesting and informative article on Bianchi .

It has been 40+ years since I rode a Bianchi Competitone as a young lad. I was searching the net for my old “love” bicycle and discovered your fine article . You just confirmed what brand of bike to try to find…….BIANCHI…….

Reguards , Jack Brooks

[…] Sales dwindled and despite production efficiencies initiated in the late '80s, by 1992 Gitane felt compelled to merge with Peugeot and BH Cycles to form Cycleurope. Gitane subsequently found itself making bikes branded as Peugeots and even Raleighs for the domestic market. Eight years later a Swedish company bought both Cycleurope and Bianchi, and assigned Bianchi the continuing role of making race bicycles. […]

I have a early 1980’s Schwinn Sprint 26′ 10 speed everything original. A true classic in mint condition, looking for buyer.

Hi Nicholas,

Thanks for the question. While I’m not sure how Kurt would answer, you might want to check out Steve Maas’ restoration pages at http://www.nonlintec.com/bikepages/. He takes a closer look at ths topic than many others.

Also, have a look at the products sold by Eastwood Company (under “Tools” on right column). They generally have very good paint related restoration products.

Cheers,

Eric

i was just wondering how you applied the paint and exatly what kind of paint you used. thank you

nicholas