About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

About Ebykr

Ebykr celebrates classic and vintage lightweight bicycles through provoking imagery and opinion. Let's roll together!

In the historical annals of cycling, one name is etched deeper than most any other: Bianchi. Founded in a Milanese workshop in 1885, it is not only the world’s oldest operating bicycle manufacturer, but a living, breathing legend cast in steel and adorned in celeste. Its story is one of relentless innovation, legendary racing triumphs and dramatic resilience, predominantly driven by the singular vision of its founder, Edoardo Bianchi – an orphan who rose to build a mechanical empire that extended well beyond bicycles. This is a narrative that traces the arc of that empire and the man behind it: its ascent fueled by the synergy between racing and marketing, its expansion into motorcycles and automobiles, its near-total collapse in the ashes of World War II, and its ultimate rebirth as a pure and enduring icon of cycling.

While still having some fun together, this narrative seeks to answer a central question: How did a small Italian workshop grow into a global symbol of engineering excellence and competitive success, and how did it survive the forces that dismantled so many of its peers? The journey begins in the bustling streets of late 19th-century Milan, where a revolution in personal transport was just beginning. Thankfully for us cycling aficionados, Edoardo Bianchi was just getting started himself, and rather quickly at that…

In the late 19th century, Milan was a crucible of industrial ambition, not unlike Coventry in England or Saint-Étienne in France. Amid the growing demand for personal transportation, a young mechanic with a sharp mind and gift for innovation was poised to make his mark (or marque?!). Edoardo Bianchi, born in Milan on July 17, 1865, possessed a special resolve built on hardship. Orphaned and taken in by the Martinitt institution, the experience forged a bond so profound that he would dedicate a percentage (purportedly 10%) of his company’s profits to them for the rest of his life.

In 1885, at just 20 years old, Edoardo opened his first mechanical workshop at No. 7 Via Nirone. The shop was a hive of eclectic activity, its scope already extending far beyond bicycles. The signs out front advertised work on velocipedes, phonographs and sewing machines. Inside, he fixed scales and wheelchairs, and even produced surgical instruments and electric bells. But it was in the assembly of bicycles, by then already in high demand, that his genius truly emerged. Initially using spare parts from England and France, he soon began applying his own modifications to improve the designs of others, eventually producing a bicycle entirely his own.

Bianchi’s early success with bicycles was driven by pivotal shifts in technology. He quickly moved away from the awkward, high-wheeled velocipedes of the era, embracing the safer and more efficient “safety” bicycle design with two equal-sized wheels. Even so, several compromises were made early on to accommodate the rapidly changing styles of the day:

Bianchi’s most crucial early innovation came in 1888 when he became the first bicycle manufacturer in Italy to adopt John Boyd Dunlop’s revolutionary invention: the pneumatic tire with an inner tube. This made the ride much smoother, softening the bumps of harsh cobblestone roads, and immediately set Bianchi’s bikes apart from other early Italian manufacturers like Prinetti & Stucchi and Ceirano, who preceded more familiar marques like Legnano, Umberto Dei and Atala.

Bianchi’s reputation for quality and innovation soon reached the highest echelons of Italian society. In 1895, Bianchi was summoned to the royal villa of Monza to teach Queen Margherita how to ride a bicycle. With characteristic ingenuity, he modified a house-made frame to accommodate her wide skirts, effectively creating the first purpose-built women’s bicycle. This royal appointment earned him the prestigious title of “Supplier of the Real House,” granting him permission to use the Savoy red-crusader coat of arms on his products – a powerful mark of quality and prestige. Other international technical and design awards followed, including royal recognition from: France, Portugal and Astoria.

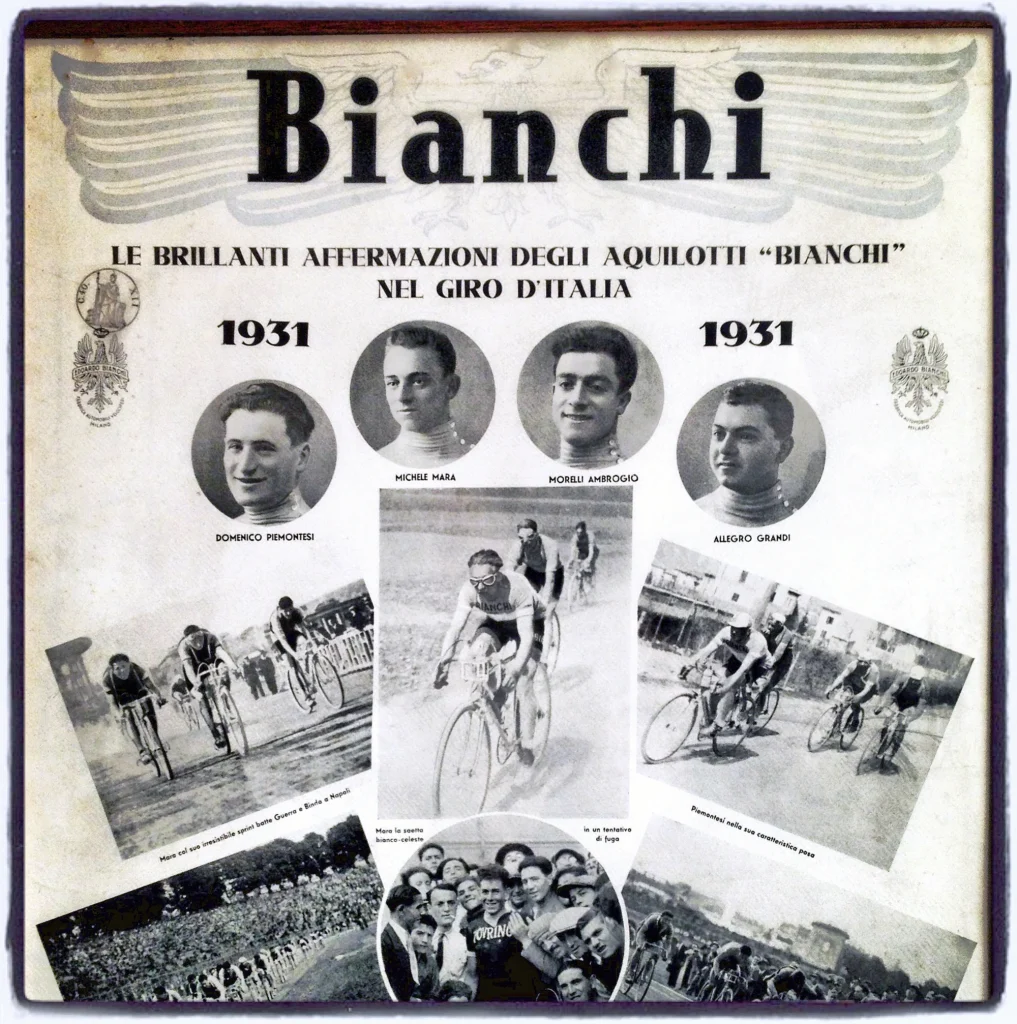

From the beginning, Bianchi also understood the link between competitive success and brand reputation. He established the famous “Reparto Corse” (or “Racing Department”) business unit in 1896 and the company scored its first major victory in 1899 when Giovanni Fernando Tomaselli won the Grand Prix de la Ville in Paris. This triumph was a clear signal of the founder’s industrial and competitive ambitions, which were already looking beyond the world of bicycles toward the new frontier of motorized transport. Whether this was more helpful or not to the company’s bicycle-making endeavors remains an open question, with advantages (capital resources, innovative scale, customer reach) and disadvantages (costly conglomeration, inefficient operations, disconnected offerings) on both sides as you will see.

The early 20th century was a period of explosive growth and ambitious diversification for the Bianchi company. Leveraging its mastery of mechanics, Bianchi grew from its cycling roots to conquer the new and expanding markets for motorcycles and automobiles, transforming itself into a vast mechanical-industrial empire. This era was defined by a series of groundbreaking innovations that cemented the company’s reputation as a technical pioneer.

Key technological advancements of the period included:

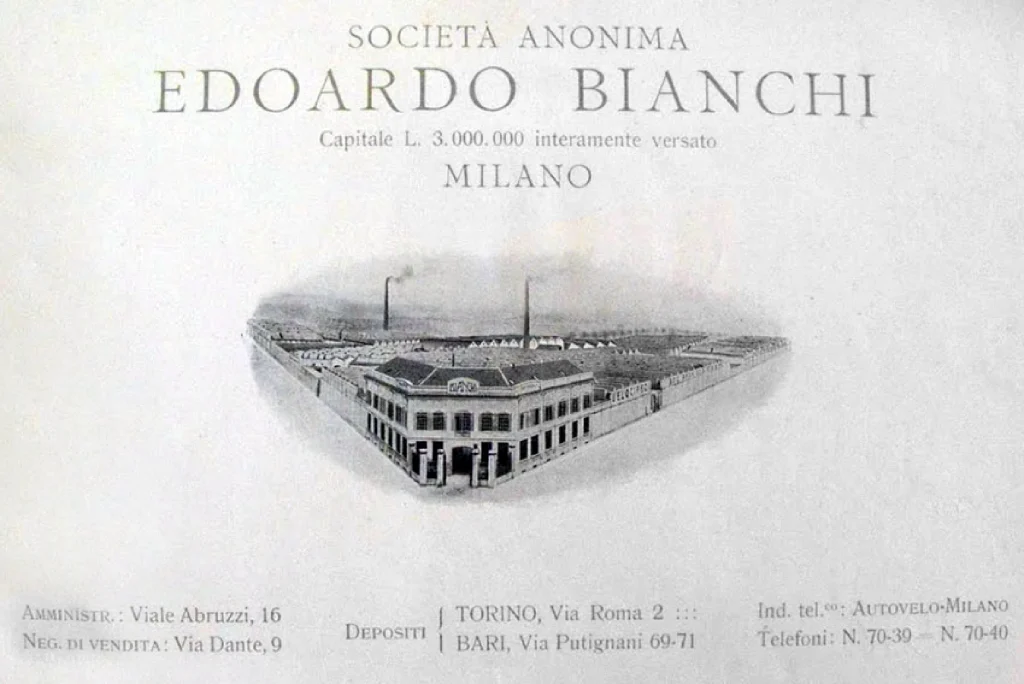

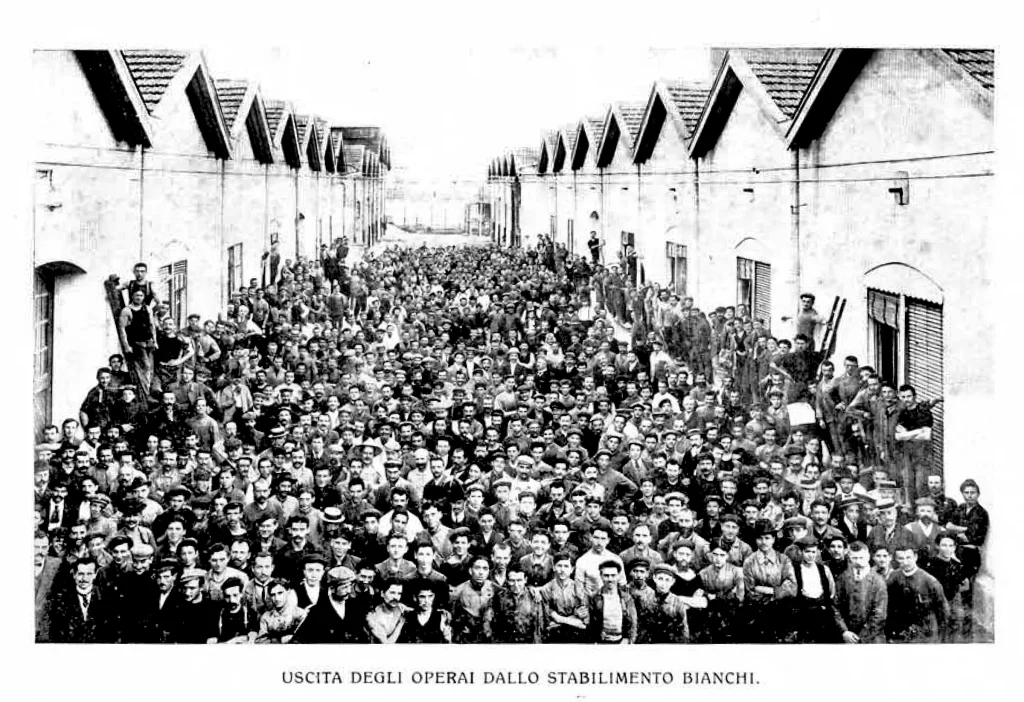

The company’s expansion into motorized vehicles was rapid and comprehensive. Motorcycle production began in 1897 and by 1900, the first Bianchi cars and motorized tricycles appeared. By 1905, Bianchi had become a joint stock company, and by 1909 it was even producing aviation engines. The scale of this growth was immense: in 1914 alone, Bianchi produced an astonishing 45,000 bicycles, 1,500 motorcycles and 1,000 cars.

One wonders what could have been done were those efforts reserved exclusively for bicycles, with that 45,000 unit production figure at Bianchi roughly in line with other leading American and European marques at the time, including: Pope Manufacturing/Columbia (100,000+), Raleigh (60,000+), Schwinn (50,000+), Peugeot (40,000-50,000), BSA (30,000-40,000) and Adlerwerke/Adler (30,000+), with many other manufacturers making bikes around then.

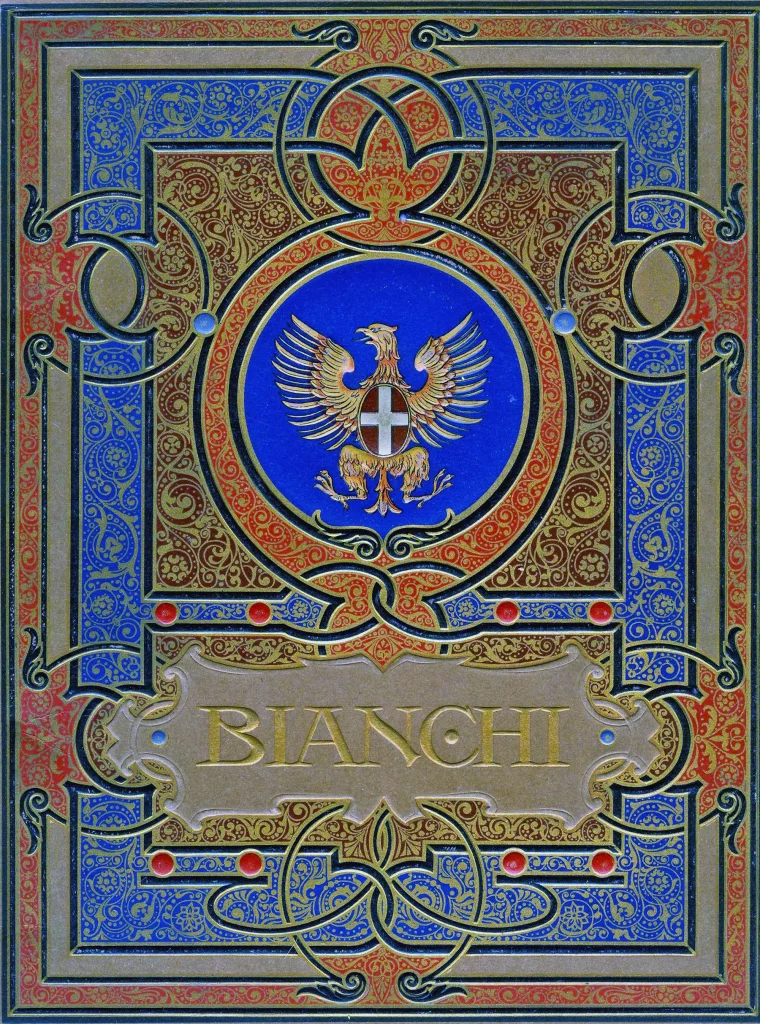

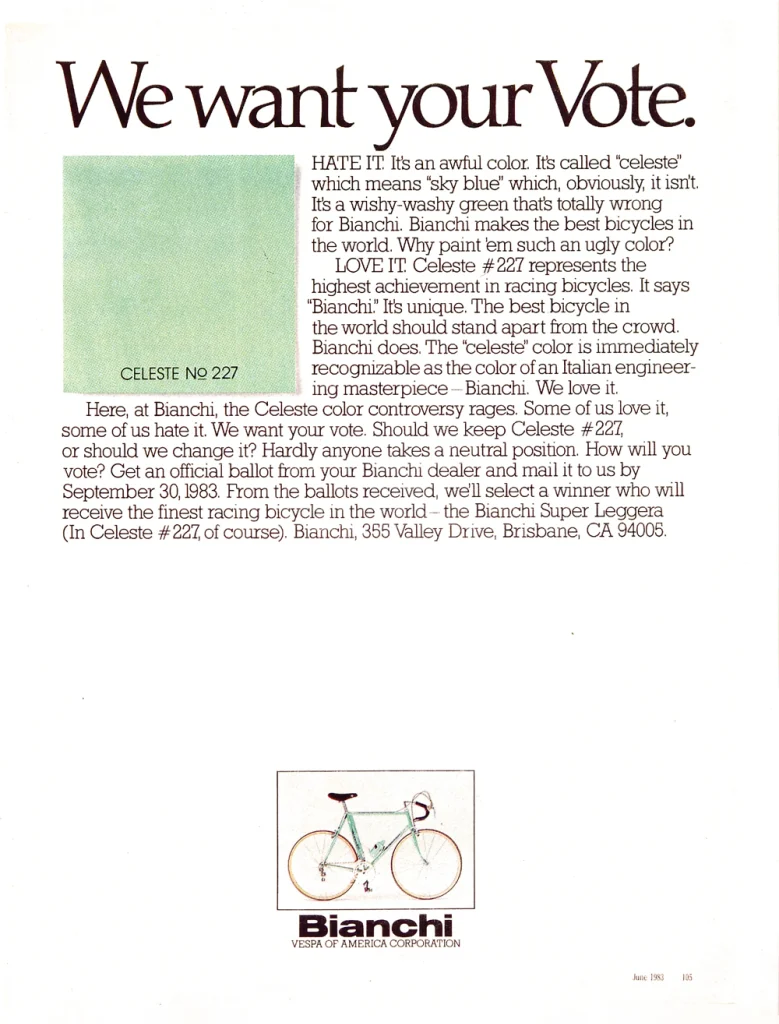

This pre-War period also saw the formalization of the early Bianchi brand and visual identities. The first registered trademark, filed in 1901, featured a crowned eagle. This powerful symbol, harkening back to the eagles of the ancient Roman legions, came to represent the company’s strength and vision. The company understood the power of its symbol, going so far as to mythologize it in a 1927 short story where the bicycle itself convinces the majestic eagle of its right to bear the iconic image – a testament to the brand’s early mastery of narrative. It was also during this era, in 1913, that the famous “celeste” color first appeared on Bianchi frames, though it would not become the brand’s signature hue until the 1940s.

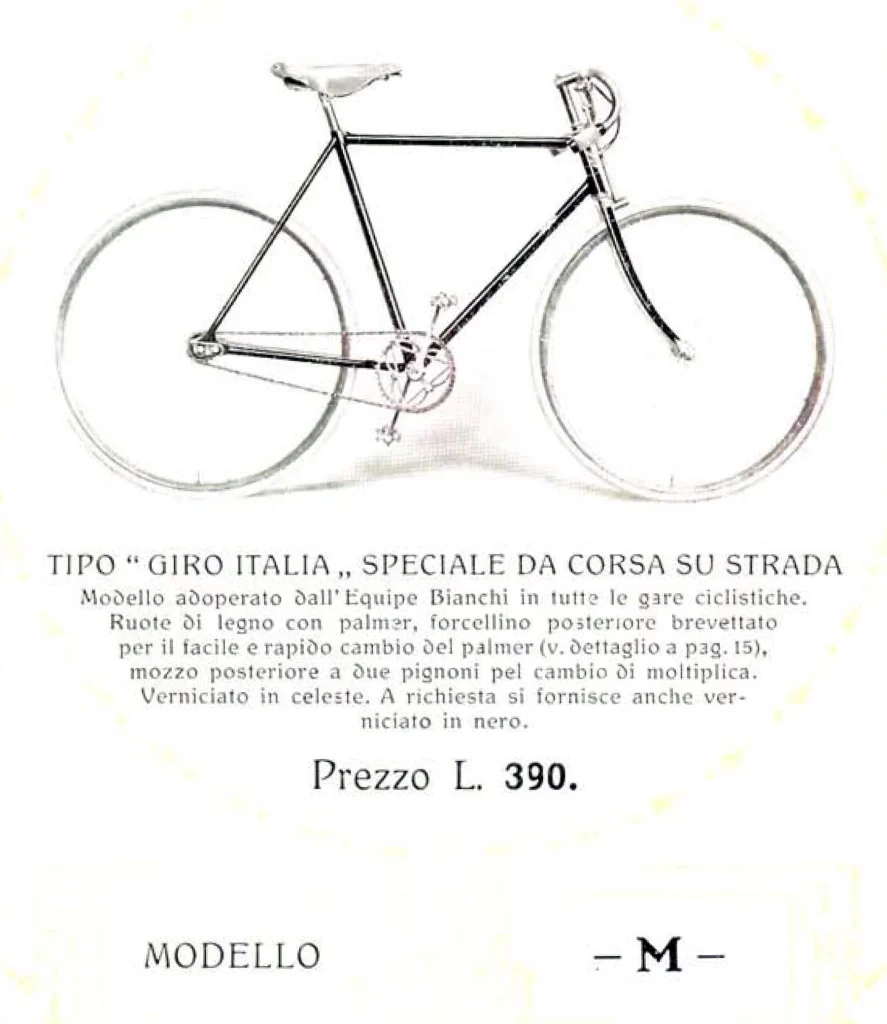

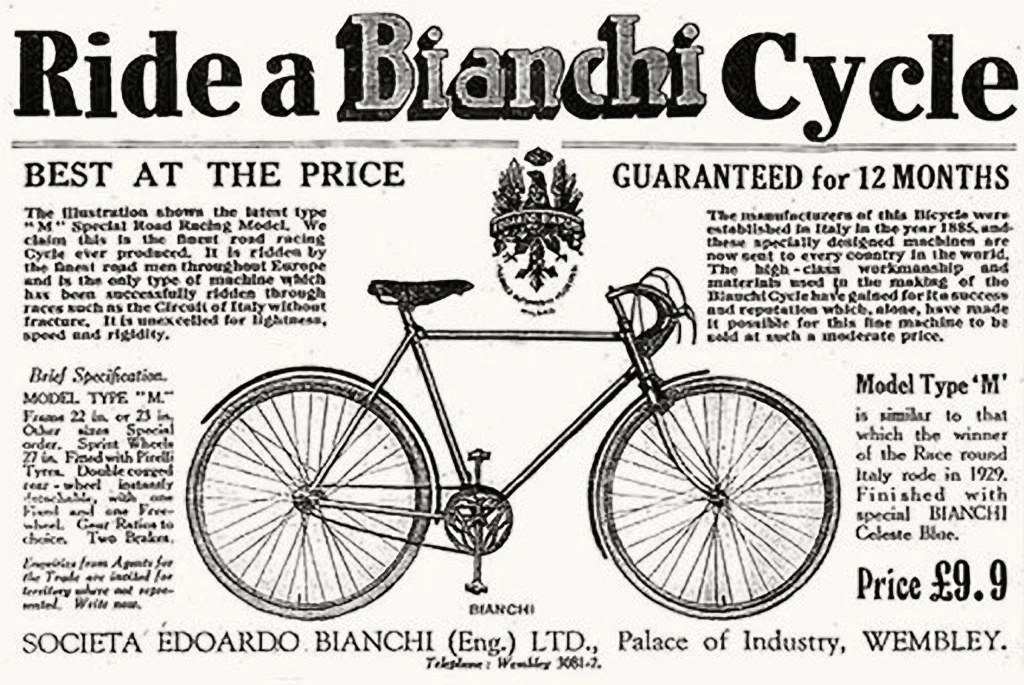

One bicycle model in particular seems to capture all of this change and hope: the “Giro d’Italia” Type M Model. The Type M would become among the most significant bikes in the company’s long, storied history. Spanning nearly two decades (which is practically an eternity in bicycle time), this model’s evolution is something of a showcase of early 20th-century technology.

The Transition: In its earliest iterations, the Type M relied on pad brakes (also known as buffer brakes) and featured adjustable dropouts designed to accommodate double-sided rear hubs equipped with two sprockets. To change gears, riders utilized “butterfly” cockerels (wingnuts), which allowed them to manually adjust the wheel position and manipulate the chain tension, a process that underscored the tactile, mechanical nature of racing before the advent of modern derailleurs and then mobile service personnel and now wireless shifting systems.

Modernization: By 1922, the Type M underwent a significant technological leap with the introduction of Bowden brakes and the freewheel, which replaced the more restrictive single and then double fixed gear setups of the past. This modernization reached its peak in 1928 with the addition of integrated oilers for the drivetrain, specialized ports that allowed for the continuous lubrication of internal components, ensuring freewheel operation remained efficient during the grueling distances of the early Giro d’Italia.

Materiality: Highlighting its role as a “bridge” between eras, the Type M offered riders a choice between traditional wooden rims or modern steel rims. While wooden rims were long favored by professional racers for their lightness and ability to dampen road vibrations on harsh terrain, the optional steel rims provided a more durable and cost-effective alternative for the burgeoning market of amateur enthusiasts and utility riders.

In the aftermath of World War I, Bianchi adapted to a changing market by focusing on less expensive, more reliable cars and motorcycles. This strategy allowed for significant penetration into both markets. Similarly, between 1924 and 1938, the company held the largest share of the booming Italian bicycle market. By the late 1930s, Bianchi was an undisputed industrial giant, a testament to Edoardo Bianchi’s relentless drive. Yet as the world marched toward another global conflict, the empire he had built would soon be tested to its breaking point.

The end of World War II presented Bianchi with its greatest existential threat. Its factories lay devastated by bombings, its visionary founder was soon gone (more on that below) and the economic landscape of Italy had been irrevocably altered. This period became a dramatic turning point for the company, an historic moment that would strip Bianchi down to its core and ultimately shape its modern identity.

In this time of uncertainty, Bianchi’s saving grace came in the form of a true superstar of the sport: Fausto Coppi. Known as Il Campionissimo (the Champion of Champions), Coppi had already won his first Giro d’Italia in 1940 and set the hour record on a Bianchi in 1942. After the War, his legendary status became the primary marketing engine for the entire company. Standing behind Coppi was a team of superstar frame builders from the Reparto Corse with names like Luigi Valsassina, who built his 1946 Milan-San Remo-winning frame, and Gilardi, who built his 1952 frame that carried him to dual Giro d’Italia and Tour de France victories that year, matching his performance from 1949. Coppi’s numerous victories—including five Giros and two Tours de France—were not just cycling or even sporting triumphs, they were also powerful symbols of Italian resilience and renaissance, both of which were in high demand at the time.

One of the most evocative cultural highlights of this era is that Pablo Picasso kept a Bianchi bicycle in his Vallauris studio, which was utilized between 1948 and 1955. He reportedly regarded it not just as transport, but as “one of the most beautiful and purest sculptures in the history of art.” And so there you have it: among the top-most fine artists ever to grace this good Earth loved bikes, too. This artistic validation even extended to high fashion: various sources note that legendary couture houses like Dior, Cartier and Van Cleef have reproduced the famous celeste bicycles in their own creative works over the years.

During this mid-century era, the trademark celeste color became a global icon in and of itself. Its origins are a favorite topic of debate among ardent collectors:

Behind this celeste-shaded veneer of sporting glory, though, the company itself was in turmoil. On July 3, 1946, Edoardo Bianchi died in a car accident and leadership passed to his son, Giuseppe. A massive post-war restructuring was undertaken, financed by a $1,000,000 international loan from the United States via the Bank of Milan, with an initial focus on the successful 125 2T motorcycle. The bicycle market remained flat due to raw material shortages (except for recycled Duralumin) and a glut of new, small manufacturers. Instability at Bianchi was dangerously compounded by a severe lack of cash. Exasperating the company’s capital shortage was the slow-moving Italian government’s non-payment of promised war reconstruction funds. By the early 1950s, generous profits on the books masked the reality that Bianchi had virtually no liquid funds available, which are critical to fund ongoing operations, let alone properly capitalize expansion into new markets.

But hey – since when have a few lira stopped a well-established and equally well-meaning bike company from doing the right thing?! The post-war era was about more than just selling the same old stuff as before, even for Bianchi. It was also about getting Italy moving again and creating altogether new markets wherever the company could given their capital constrained but still substantial wherewithal. Enter the Aquilmotoro in 1950. This was an engine specifically designed to be retro-mounted onto existing bicycle frames, essentially turning a standard bike into a motorized moped. Somewhat surprisingly, the Aquilmotoro represents among the few serious efforts by any maker of either bicycles or lightweight mopeds to actually bridge these two market segments with an offering designed to retrofit onto bicycles and appeal to bicycle owners looking to motorize. Perhaps bicycles and mopeds are just that different from each other, or perhaps their owners are. Either way, the Aquilmotoro stands out in this way. (And is not to be confused with the Aquilotto, which was a family of dedicated lightweight moped offerings—fixed fuel tank and all—available from Bianchi at the same time.)

By then, if not already clear, Bianchi was no longer just a workshop – it was an industrial ecosystem. To recapture a recovering Italian market, the company relied on the still-soaring reputation of Fausto Coppi to continue anchoring a sophisticated marketing strategy. This resulted in a beautifully segmented bicycle model lineup designed to offer a piece of the “Campionissimo” legacy to every level of rider.

For the vintage connoisseur, this era likely represents the peak of Bianchi’s steel lineage, defined by four distinct and complete bicycle lines:

Despite the company hitting its peak steel bicycle manufacturing years during this time period (or because of hitting this peak, if you are a regular Ebykr reader), several interconnected factors nonetheless converged to push the Bianchi corporate empire toward collapse. These included:

By 1964, the situation had become dire. In a bitter irony, Bianchi found itself producing parts for Fiat, the very company whose 500 model was gutting its business. To forestall bankruptcy, General Manager Ferrucio Quintavalle negotiated a 40% settlement of its debt with creditors. The arrangement involved the liquidation of all remaining non-cycling divisions, including the small but well-respected boat manufacturing division, Bianchi Nautica. It is unclear if the company’s aircraft engine manufacturing division–active since 1909–was also part of this liquidation event or had already wound down by then. (Which brings to mind the Mavic Air Department some 20 years later, which was that company’s much-shorter-lived aircraft manufacturing division.) Out of the settlement, a single entity was allowed to survive independently: Officine Metallurgiche Edoardo Bianchi SpA, the bicycle division.

Stripped of its vast industrial empire, Bianchi had been forced back to its foundation. No more mopeds, motorcycles, cars, boats or planes. From these ashes, a new legend built exclusively on two human-powered wheels was set to rise. Right on cue, the company’s 1965 catalog featured an incredibly diverse range of 19 different racing bikes, along with many other styles from industrial delivery bikes to comfort bikes for “women and priests.” Call it a back to basics strategy on steroids, approved by the heavens above. (What a weird mental image, right?!)

The period from the mid-1960s onward marked a true renaissance for Bianchi. Free from the motorized burdens that had nearly destroyed it, the company entered an era of renewed focus, re-establishing its dominance in the world of professional cycling and solidifying its identity as a pure, high-performance bicycle brand. The face of this rebirth was Felice Gimondi, Italy’s new cycling hero, who inherited the legacy of Fausto Coppi seamlessly and propelled the company’s image to new levels of recognition.

The reborn company also underwent significant corporate and manufacturing changes. It was taken over by industrialist Angelo Trapletti and a modern factory was inaugurated in Treviglio in 1967. After 13 years under his leadership, Bianchi became part of the Piaggio industrial group in 1980, a move that provided stability and resources for the coming decades, even among a portfolio of motorized brands.

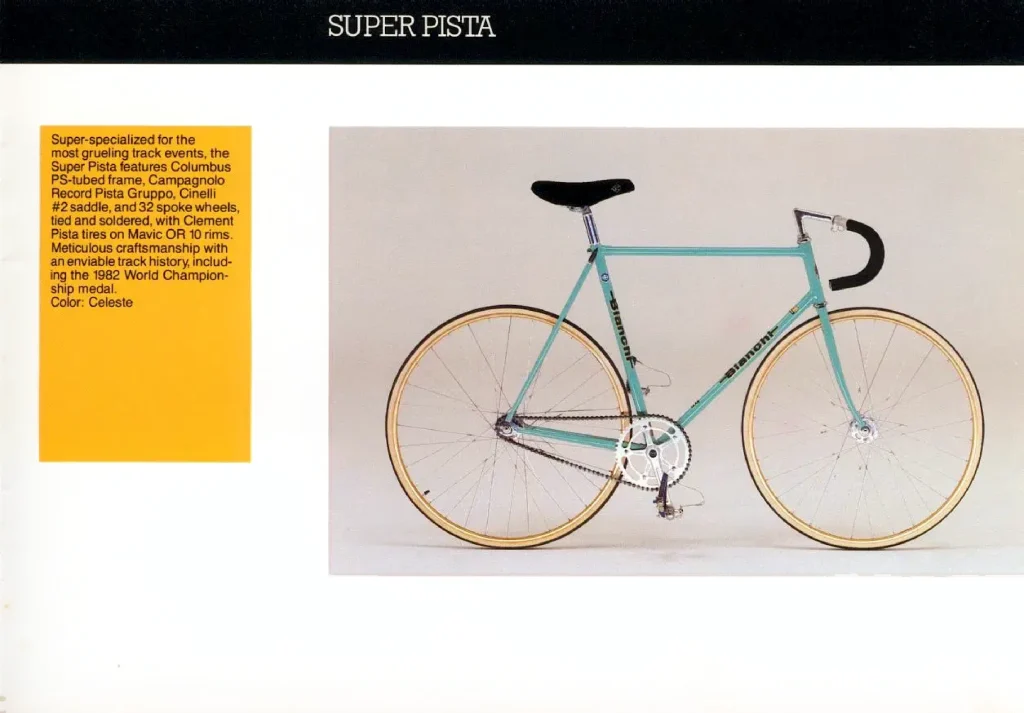

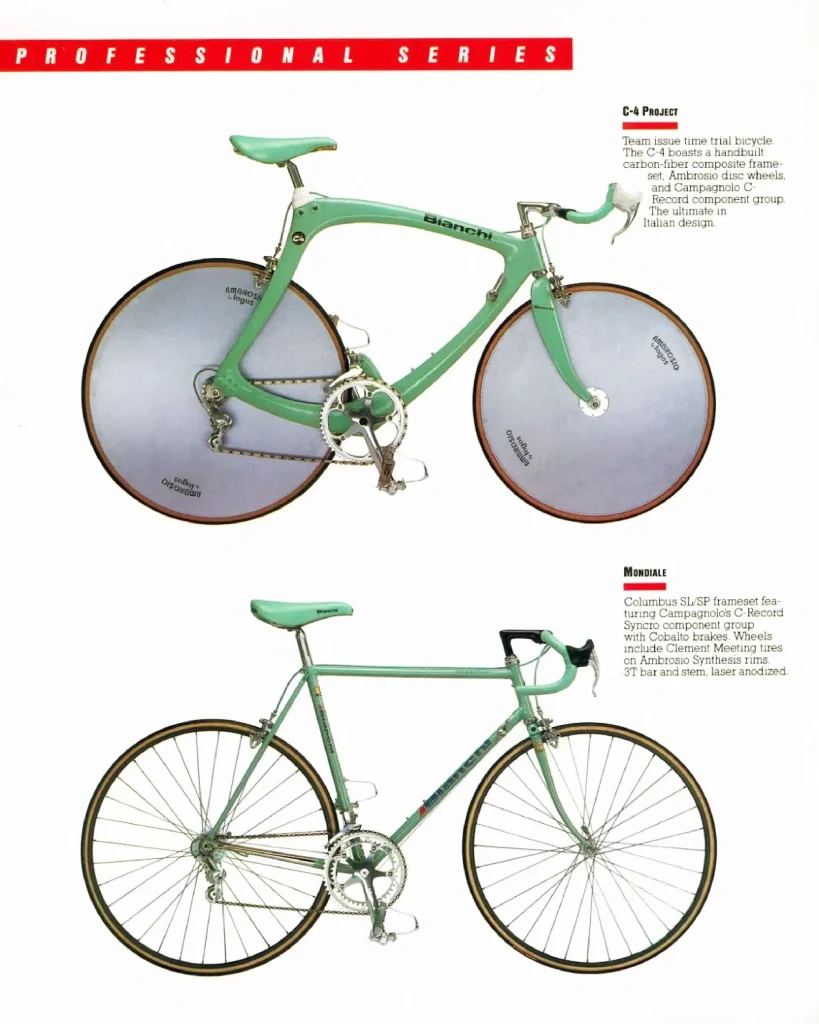

This era was defined not only by its champions, but also by the iconic machines they rode. Bianchi’s “Reparto Corse” continued to produce some of the most advanced and celebrated bicycles in the world, building on a legacy of performance that stretched back to Coppi’s era. Here are some of our favorite Bianchi racing models at Ebykr:

Evolution of Iconic Racing Models

| Model Name | Key Years | Noteworthy Features |

| Folgore | 1940 | The pre-war benchmark. It was the first to adopt the Campagnolo two-lever gearbox (Cambio Corsa), a complex system that required the rider to back-pedal while manipulating the chain between sprockets. |

| Paris-Roubaix | 1950-1951 | Originally named the Folgorissimo, this model was renamed to honor Coppi’s victory in “The Hell of the North.” It featured Universal 5501 brakes, Nisi aluminum rims, a Brooks or Aquila saddle, and a move from 4-speed to 5-speed freewheels. |

| Tour de France | 1952-1953 | Celebrating Coppi’s 1952 yellow jersey, this model was equipped with the Campagnolo Gran Sport derailleur, signaling the transition to modern shifting. It featured an Ambrosio stem and aluminum handlebars – a shift away from the heavy steel cockpits of the previous decade. |

| Campione del Mondo | 1953-1954 | Introduced to commemorate Coppi’s historic 1953 World Championship victory in Lugano, this model forever linked the Bianchi name to the prestige of the rainbow jersey. It represents a technical peak of the mid-century era, following the successful lineage of the Paris-Roubaix and Tour de France models that defined the Campionissimo’s golden years. For the modern collector, it remains a quintessential racing thoroughbred that captured the soul of Italian cycling at the height of its international dominance. |

| Specialissima | 1958-onward | Perhaps the most iconic name in the Bianchi stable, the 1958 Specialissima arrived as a pure racing thoroughbred. Assembled with the Campagnolo Record groupset, it featured a key technical update: the seatpost diameter was increased to 27.2 mm (up from the previous 25 mm) to increase rigidity. This model would become the weapon of choice for the legendary Salvarani team in the 1960s. |

| Centennial | 1985 | This iconic flagship was released as a limited commemorative tribute to celebrate the company’s 100th anniversary. It is widely considered one of the most sought-after vintage lightweights in existence, distinguished by its exquisite lugged steel craftsmanship and the signature celeste finish. Featuring gorgeous chrome lugs and premium tube sets, the Centenario serves as a masterful bridge between the classical heritage of Edoardo Bianchi’s steel empire and the onset of the modern era. |

By the end of the 1980s, Bianchi had successfully navigated its most perilous decades as a going concern. It had shed its diversified past to rediscover its soul, emerging stronger, more focused and ready to enter the modern era as a pure and celebrated legend of the cycling world. Somewhat ironically and very much contradictory to the market norm, Bianchi seemed to benefit—at least some of its lines of bicycles—from the company’s move to Japanese manufacturing in the late 1980s. While “true Italian” purist types may have scoffed at these models, their quality and craftsmanship were actually superior to many contemporary Italian-made models. This fact was difficult to conceal among discerning, value-conscious buyers who accelerated the company’s (and industry’s) manufacturing transition toward Asia.

The first century of Bianchi is a remarkable story of ascent, crisis and rebirth. From Edoardo Bianchi’s humble workshop on Via Nirone, an industrial giant was born – one that built not just bicycles, but an entire ecosystem of personal and shared transport. When that empire crumbled due to a confluence of factors, the company’s survival depended on a painful but necessary return to its core. This journey reveals that the foundational tenets established by its founder were the very things that ensured its continuation.

The legacy of Bianchi is built on pillars that have remained constant through a century of turmoil: a relentless drive for technical innovation, an unwavering passion for racing, and an iconic brand identity symbolized by the proud eagle and unforgettable celeste hue. These were the elements that allowed the company to survive when its other motorized ventures failed. The eagle, once the standard of Roman legions, now flies on the headtube of every Bianchi bicycle, carrying not an army, but over a century of Italian passion, triumph and ingenuity into every ride.

Bianchi is currently owned by Grimaldi Industri AB, a Swedish industrial group, and operates through its bicycle division, Cycleurope AB. Also included in this division are (or historically were) such storied marques as: Gitane, Peugeot, Legnano and Raleigh. Despite the corporatized ownership structure, Bianchi remains the premier brand in the Cycleurope portfolio and proudly maintains its Italian design and production heritage, with its main facilities still located in Treviglio, Italy as they have been for 60 years.

Some things are never meant to change. Bianch building great bicycles is one of them.

https://www.ebykr.com/edoardo-bianchi-bicycles-history/

https://www.ebykr.com/the-eagle-and-the-bianchi-bicycle/

https://speedreaders.info/143-edoardo_bianchi_by_antonio_gentile/

https://www.museonicolis.com/en/35297/

https://www.cyclingwest.com/july/july99/classic.html

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/F.I.V._Edoardo_Bianchi

https://theamericanmag.com/orphans/

https://www.icenicam.org.uk/articlesb/art0179.php

https://www.registrostoricobianchi.it/la-bianchi/le-auto/

http://www.ciclostileparma.it/cataloghi.html

https://www.registrostoricocicli.com/cataloghi-cicli-depoca/